tutorial, commentary, study resources, and further reading

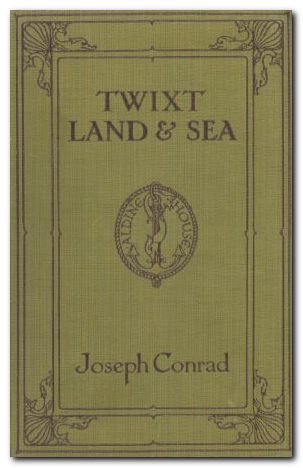

The End of the Tether was written in 1902 and collected in Youth, a Narrative and Two Other Stories, published by William Blackwood in 1902. The other stories in the trio were Youth and Heart of Darkness.

The End of the Tether – critical commentary

Story – Tale – Novella – Novel?

This narrative is too long, complex, and rich in dramatic incident to be considered a story in the modern sense of that term. Not that Conrad generally considered his shorter fictions stories: he used the tern tales to describe them. And The End of the Tether might be considered a tale – except that the term tale as a literary category is elastic and ill-defined. It can be used for any sort of shapeless narrative that falls short of a full length novel.

The End of the Tether could almost be classified as a short novel. It has a central, fully-rounded protagonist in Captain Whalley, and the secondary characters of Massy, Sterne, and Van Wyk are all fully developed with convincing psychological motivations firmly anchored to the plot.

But it seems to me that the concentration of the main theme (money) and the dramatic unity of events lends the narrative to be classified as a novella. There are no decorative or superfluous passages here. Every event is strongly related to the overall effect.

It’s true that there is no central image or symbol – unless it is the Sofala itself. It is owned by one man (Massy) who has financial problems of his own making, and it is captained by another (Whalley) who also has financial problems – caused partly by the international capitalist banking system, and partly by his obsessive desire to provide for his daughter.

The ship has faulty boilers which should have been replaced by its owner (but he has gambled away his money); the crew are a dubious collection of individuals, and one of them (a drunk) correctly predicts that the ship will be deliberately shipwrecked for the sake of the insurance money.

So the tragic hero figure (Whalley) is firmly related to the central symbol of the novella – a doomed ship which is on its last voyage. It is therefore entirely fitting in terms of the demands of dramatic unity that Whalley goes down with the ship.

The tragic hero

Whalley is a tragic hero in the classical sense that the very characteristics which make him noble and heroic – his desire to finance and protect his own daughter – are the very things that bring about his downfall. And he falls from a great height – the former captain of famous ships, with a fortune and with an island and a nautical passage named after him.

Whalley struggles to maintain his sense of honour and does the right thing for the ship and what he feels is an obligation to support his daughter – whilst he is yoked to an unscrupulous villain, a moral shirker, and a desperate antagonist who has one advantage over him: he can see what he is doing.

The main theme

Despite its setting as a maritime tale (like so many of Conrad’s other works) the essential theme of this piece is money.

Whalley has amassed a fortune through hard work and honest dealing – but it is largely swallowed up by the collapse of a bank.

He had not been alone to believe in the stability of the Banking Corporation. Men whose judgement in matters of finance was as expert as his seamanship had commended the prudence of his investments, and had themselves lost much money in the great failure.

After selling the Fair Maid he is left with a lump sum of £500 and £200 for his daughter’s dubious investment in the Australian lodging house. He is quite prudent with the £500, and ties it into the agreement with Massy for a fixed period, with strong protection clauses. But it does tie him to co-operation with a villain.

Massy on the other hand is entirely motivated by dreams of easy wealth. Having won the lottery once, he has become addicted to gambling, and his greed is such that he cannot believe that Whalley hasn’t got more than the £500. Massy wants to exhort more money from him – not to promote their business ventures, but to fuel his gambling lust.

He is prepared to shipwreck the Sofala in order to claim the insurance (as its owner) and Whalley (as its captain) is eventually prepared to go down with his ship because he cannot face his incipient blindness, which deprives him of the very skill that made his fortune in the first place.

Conrad deploys a bitterly ironic twist when Captain Whalley puts into the pockets of his own jacket the very pieces of scrap iron Massy has used to deflect the ship’s compass. Whalley knows that it is possible for bodies to resurface from the maelstrom of a sinking ship, and he does not want to survive his own watery grave.

The End of the Tether – study resources

![]() The End of the Tether – Collector’s Library – Amazon UK

The End of the Tether – Collector’s Library – Amazon UK

![]() The End of the Tether – Collector’s Library – Amazon US

The End of the Tether – Collector’s Library – Amazon US

![]() The End of the Tether – Kindle eBook

The End of the Tether – Kindle eBook

![]() The End of the Tether – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The End of the Tether – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The End of the Tether – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The End of the Tether – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The End of the Tether – Aeterna Editions – Amazon UK

The End of the Tether – Aeterna Editions – Amazon UK

![]() The End of the Tether – Aeterna Editions – Amazon US

The End of the Tether – Aeterna Editions – Amazon US

![]() The End of the Tether – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

The End of the Tether – eBook versions at Project Gutenberg

![]() Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

Joseph Conrad: A Biography – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

Routledge Guide to Joseph Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad – Amazon UK

![]() Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

Notes on Life and Letters – Amazon UK

![]() Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

Joseph Conrad – biographical notes

The End of the Tether – plot summary

Part I. Henry Whalley is captain in charge of the Sofala which makes regular trade journeys on a fixed route in the Malay archipelago. He has previously been captain of a much bigger ship, the Condor, has made famous voyages, and has been fifty years at sea, with an honourable record. But he has lost most of his money in a banking crash.

Part II. Having married off his daughter, he retired with his own ship the Fair Maid. He is much given to reminiscence about his wife (now dead) who he regarded as a shipmate. He has given his daughter a large sum of money on her marriage to a man he thinks an unsuitable choice of husband.

He is planning what he will leave to her and her children when the bank wipes out his fortune. He realises that he will have to earn a living with the Fair Maid. But he discovers that all his old business contacts in the shipping world have gone – replaced by younger people he doesn`t know. Then his son-in-law becomes a wheel-chair invalid.

Whalley cuts back on his own personal expenditure in order to send money to his daughter, but then she asks him to send her £200 to become the landlady of a boarding hose – and he doesn`t have the money.

Part III. Whalley sells the Fair Maid, after which he has £500 to invest and £200 to send to his daughter. He moves into a cheap hotel and feels both homeless and bereft.He has spent all his life in command of ships, and now feels he has nothing. He also thinks that his daughter Ivy being landlady of a boarding house is a slur on his family`s reputation.

Part IV. He wonders what employment he might secure, and fears the consequences of breaking into his £500 life savings. On meeting a government official he thinks back to his earliest days in the port when it was quite undeveloped.

Part V. He meets Captain Elliot, master-attendant of the port who brags about his government connections and complains that having three daughters is a drain on his prospects. Elliot then reveals that the Sofala is looking for a captain. It is owned by George Massy its current engineer, who bought it with winnings from the Manilla lottery. It is currently losing trade, and Massy is spending all his money gambling. Elliot suggests that the only solution would be for Massy to locate a partner who could buy into the business.

Part VI. Whalley invests his £500 in the Sofala for three years and a sixth part of the profits, with a stipulation that if anything happens the money is paid back entirely to Ivy within three months. The narrative then rejoins the opening of the story as the Sofala approaches Batu Bera, and Whalley`s agreement (almost three years old) has six weeks left to run.

Part VII. Massy is a cantankerous owner who thinks everybody else is a fool and beneath his contempt. He bitterly resents Whalley being the ship’s captain. The second mate Jack is a drunken loner whose occasional binges result in imprecations for all members of the Sofala crew past and present with the exception of Massy.

Part VIII. Whalley concentrates on the difficulty of getting the ship across the bar near their destination – and does so with very little depth to spare. Massy threatens to sack Whalley for incompetence. Massy has included a dismissal clause in their agreement for intemperance, and has been aggrieved to discover that Whalley does not drink at all. He also believes that Whalley must have lots more money and wants him to invest more in their joint venture.

Part IX. The ambitious and sneaky chief mate Sterne tries to get promotion from Massy by criticising Whalley. Sterne has been on the Sofala hoping to profit from what seems to him an odd state of affairs. Then when the ship is being navigated through an archipelago, he makes what he believes is an important discovery from which he might profit.

Part X. He arrives at his discovery via his peevish contemplation of Whalley and his loyal henchman, the native Serang – likening them to a whale and its pilot fish. Sterne thinks Whalley is perpetrating a giant fraud, motivated by greed, He thinks the Serang is secretly in charge and that Whalley is losing his sight. Sterne thinks it is time to act, but isnt sure what to do and cannot trust anyone else.

Part XI. Sterne confronts Massy and asks for the job of master of the Sofala. Massy is eaten up by his obsession with lottery numbers, buying tickets for which has brought about his financial downfall. He even resents the wages he has to pay his own crew. Most of all he resents Whalley and their agreement. The ship finally docks at Batu Bera and is met on shore by Mr Van Wyk.

Part XII. Former sailor Van Wyk has established a thriving tobacco plantation- but he relies on regular visits from the Sofala for news and supplies, including his mail. Because the ship is late, Van Wyk blames Massy, and Whalley goes to dinner at Van Wyk’s house, hoping to placate him. Over the years the two naval men have got on well together: Whalley sees improvements everywhere, whereas Van Wyk is slightly more sceptical. Despite these differences, the two men are good friends.

Part XIII. Sterne has attempted to poison Van Wyk’s mind against Whalley, hoping he will be sacked fromthe ship, leaving him to take over its captaincy. But Van Wyk thinks Sterne is a sneak and a trouble-maker. Over dinner, Whalley reveals to Van Wyk that he is going blind. He has been concealing the fact for the sake of the money he is going to send to his daughter.

Hoping to head off Sterne and protect his friend Whalley, Van Wyk visits the Sofala and suggests to Sterne that he might advance a loan and join Whalley for the ship’s last trip under the agreement. Massy stays on board thinking about winning lottery numbers and listening to the second mate’s drunken ramblings as he predicts that Massy will sink the old ship to collect the insurance money.

Part XIV. Massy harasses Whalley again to extend their partnership. He cannot believe that Whalley hasn’t got more money than £500. Massy is motivated entirely by a desire for easy welth and even plans to gamble on the lottery with a winning number that has come to him in a dream. Whalley meanwhile worries about getting the £500 to his daughter.

Massy plans a shipwreck and plants scrap iron in his coat next to the ship’s compass during a night watch. Whalley discovers the coat just as the ship strikes a reef. The crew escape in lifeboats. Feeling he has lost everything, Whalley transfers the scrap iron into his own coat and goes down with the ship.

At the following inquest no blame is attached to Whalley. Massy goes off with the insurance money to gamble in Manilla, and Ivy receives a letter confirming that her father is dead.

Joseph Conrad – video biography

The End of the Tether – principal characters

| Henry Whalley | experienced sea captain and widower |

| Ivy | his daughter |

| Captain Ned Elliot | master-attendant of port |

| George Massy | engineer and owner of the Sofala |

| Sterne | scheming first mate on the Sofala |

| Jack | drunken second mate on the Sofala |

| Mr Van Wyk | a Dutch ex-naval tobacco planter |

first edition, Blackwood 1902

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Joseph Conrad’s writing table

Further reading

![]() Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

Amar Acheraiou Joseph Conrad and the Reader, London: Macmillan, 2009.

![]() Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Jacques Berthoud, Joseph Conrad: The Major Phase, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

Muriel Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Poland’s English Genius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

Harold Bloom (ed), Joseph Conrad (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2010

![]() Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

Hillel M. Daleski , Joseph Conrad: The Way of Dispossession, London: Faber, 1977

![]() Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Daphna Erdinast-Vulcan, Joseph Conrad and the Modern Temper, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

![]() Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

Aaron Fogel, Coercion to Speak: Conrad’s Poetics of Dialogue, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1985

![]() John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

John Dozier Gordon, Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1940

![]() Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

Albert J. Guerard, Conrad the Novelist, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958

![]() Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

Robert Hampson, Joseph Conrad: Betrayal and Identity, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Language and Fictional Self-Consciousness, London: Edward Arnold, 1979

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

Jeremy Hawthorn, Joseph Conrad: Narrative Technique and Ideological Commitment, London: Edward Arnold, 1990

![]() Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Sexuality and the Erotic in the Fiction of Joseph Conrad, London: Continuum, 2007.

![]() Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

Owen Knowles, The Oxford Reader’s Companion to Conrad, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990

![]() Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

Jakob Lothe, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008

![]() Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

Gustav Morf, The Polish Shades and Ghosts of Joseph Conrad, New York: Astra, 1976

![]() Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

Ross Murfin, Conrad Revisited: Essays for the Eighties, Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1985

![]() Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

Jeffery Myers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, Cooper Square Publishers, 2001.

![]() Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

Zdzislaw Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007.

![]() George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

George A. Panichas, Joseph Conrad: His Moral Vision, Mercer University Press, 2005.

![]() John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

John G. Peters, The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

![]() James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

James Phelan, Joseph Conrad: Voice, Sequence, History, Genre, Ohio State University Press, 2008.

![]() Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

Edward Said, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography, Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966

![]() Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

Allan H. Simmons, Joseph Conrad: (Critical Issues), London: Macmillan, 2006.

![]() J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

J.H. Stape, The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996

![]() John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, Arrow Books, 2008.

![]() Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

Peter Villiers, Joseph Conrad: Master Mariner, Seafarer Books, 2006.

![]() Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

Ian Watt, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, London: Chatto and Windus, 1980

![]() Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Cedric Watts, Joseph Conrad: (Writers and their Work), London: Northcote House, 1994.

Other writing by Joseph Conrad

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

Lord Jim (1900) is the earliest of Conrad’s big and serious novels, and it explores one of his favourite subjects – cowardice and moral redemption. Jim is a ship’s captain who in youthful ignorance commits the worst offence – abandoning his ship. He spends the remainder of his adult life in shameful obscurity in the South Seas, trying to re-build his confidence and his character. What makes the novel fascinating is not only the tragic but redemptive outcome, but the manner in which it is told. The narrator Marlowe recounts the events in a time scheme which shifts between past and present in an amazingly complex manner. This is one of the features which makes Conrad (born in the nineteenth century) considered one of the fathers of twentieth century modernism.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of the process of Imperialism. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement, and it is based on his own experiences as a sea captain. This volume also contains ‘An Outpost of Progress’ – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2013

Joseph Conrad web links

Joseph Conrad at Mantex

Biography, tutorials, book reviews, study guides, videos, web links.

Joseph Conrad – his greatest novels and novellas

Brief notes introducing his major works in recommended editions.

Joseph Conrad at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of formats.

Joseph Conrad at Wikipedia

Biography, major works, literary career, style, politics, and further reading.

Joseph Conrad at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production notes, box office, trivia, and quizzes.

Works by Joseph Conrad

Large online database of free HTML texts, digital scans, and eText versions of novels, stories, and occasional writings.

The Joseph Conrad Society (UK)

Conradian journal, reviews. and scholarly resources.

The Joseph Conrad Society of America

American-based – recent publications, journal, awards, conferences.

Hyper-Concordance of Conrad’s works

Locate a word or phrase – in the context of the novel or story.

More on Joseph Conrad

Twentieth century literature

Joseph Conrad complete tales

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten.

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) is a classic novella – half way between a long story and a short novel. It’s a wonderfully condensed tale of the relationship between art and life, love and death. Venice provides the background for the story of a famous German writer who departs from his usual routines, falls in love with a young boy, and gets caught up in a subtle downward spiral of indulgence. The novella is constructed on a framework of references to Greek mythology, and the unity of themes, form, and motifs are superbly realised – even though Mann wrote this when he was quite young. Later in life, Mann was to declare – ‘Nothing in Death in Venice was invented’. The story was turned into a superb film by Luchino Visconti and an opera by Benjamin Britten. Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities.

Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd (1856) deals with a tragic incident at sea, and is based on a true occurence. It is a nautical recasting of the Fall, a parable of good and evil, a meditation on justice and political governance, and a searching portrait of three men caught in a deadly triangle. Billy is the handsome innocent, Claggart his cruel tormentor, and Captain Vere the man who must judge in the conflict between them. The narrative is variously interpreted in Biblical terms, or in terms of representations of male homosexual desire and the mechanisms of prohibition against this desire. His other great novellas Benito Cereno, The Encantadas and Bartelby the Scrivener (all in this collection) show Melville as a master of irony, point-of-view, and tone. These fables ripple out in nearly endless circles of meaning and ambiguities. Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments.

Artistically, the novella is often unified by the use of powerful symbols which hold together the events of the story. The novella requires a very strong sense of form – that is, the shape and essence of what makes it distinct as a literary genre. It is difficult to think of a great novella which has not been written by a great novelist (though Kate Chopin’s The Awakening might be considered an exception). Another curious feature of the novella is that it is almost always very serious. It’s equally difficult to think of a great comic novella – though Saul Bellow’s excellent Seize the Day has some lighter moments. Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976.

Seize the Day (1956) focusses on one day in the life of one man, Tommy Wilhelm. A fading charmer who is now separated from his wife and his children, he has reached his day of reckoning and is scared. In his forties, he still retains a boyish impetuousness that has brought him to the brink of havoc. In the course of one climatic day, he reviews his past mistakes and spiritual malaise. Some people might wish to argue that this is a short novel, but it is held together by the sort of concentrated sense of unity which is the hallmark of a novella. It is now generally regarded as the first of Bellow’s great works, even though he went on to write a number of successful and much longer novels – for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976. Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends.

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (1897) is a classic novella, and a ghost story which defies easy interpretation. A governess in a remote country house is in charge of two children who appear to be haunted by former employees who are now supposed to be dead. But are they? The story is drenched in complexities – including the central issue of the reliability of the person who is telling the tale. This can be seen as a subtle, self-conscious exploration of the traditional haunted house theme in Victorian culture, filled with echoes of sexual and social unease. Or is it simply, “the most hopelessly evil story that we have ever read”? This collection also includes James’s other ghost stories – Sir Edmund Orme, Owen Wingrave, and The Friends of the Friends. The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella.

The Aspern Papers (1888) also by Henry James, is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s private correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer seeks a husband for her plain niece, whereas the potential purchaser of the letters she possesses is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who wins out? Henry James keeps readers guessing until the very end. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in the outcome. This collection of stories also includes The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion which is another classic novella. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902) is a tightly controlled novella which has assumed classic status as an account of late nineteenth century imperialism and the colonial process. It documents the search for a mysterious Kurtz, who has ‘gone too far’ in his exploitation of Africans in the ivory trade. The reader is plunged deeper and deeper into the ‘horrors’ of what happened when Europeans invaded the continent. This might well go down in literary history as Conrad’s finest and most insightful achievement. It is certainly regarded as a classic of the novella form, and a high point of twentieth century literature – even though it was written at its beginning. This volume also contains the story An Outpost of Progress – the magnificent study in shabby cowardice which prefigures ‘Heart of Darkness’. The differences between a story and a novella are readily apparent here if you read both texts and compare them. Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.

Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is the account of a young salesman who wakes up to find he has been transformed into a giant insect. His family are bewildered, find it difficult to deal with him, and despite the good human intentions struggling underneath his insect carapace, they eventually let him die of neglect. He eventually expires with a rotting apple lodged in his side. This particular collection also includes Kafka’s other masterly transformations of the short story form – ‘The Great Wall of China’, ‘Investigations of a Dog’, ‘The Burrow’, and the story in which he predicted the horrors of the concentration camps – ‘In the Penal Colony’.

The Lost Steps

The Lost Steps The Chase

The Chase

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller