tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

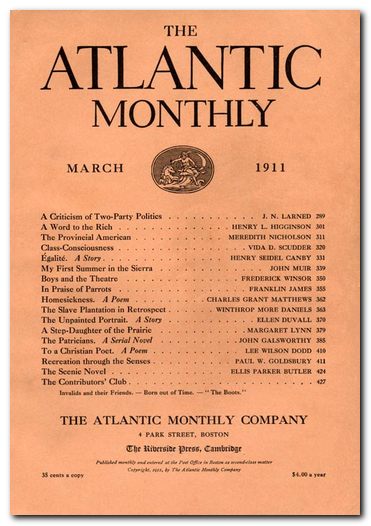

The Madonna of the Future first appeared in The Atlantic Monthly for March 1873. It was reprinted two years later as part of James’s first book, The Passionate Pilgrim and Other Tales, published by Osgood in Boston, 1875. It became a very popular tale and was frequently reprinted in collections of James’s stories.

Raphael – The Madonna of the Chair (1513-1514)

The Madonna of the Future – critical commentary

James wrote a number of stories about art, artists, their achievements, and their reputations – both whilst alive and after their death. The Madonna of the Future is about a would be artist. Theobald has an enormous reverence for the world of Art, and Italian Renaissance painters in particular. He is well informed about the history and the technical details of what they have produced.

He takes what we would now call a high romantic view of art – that an appreciation of its values offers entrance into a quasi-religious and transcendental realm which can sustain the individual even whilst they might live in reduced circumstances or even poverty. This is a view of art which John Carey discusses at some length in his study What Good are the Arts?

Theobald has worshipped at this shrine of art for years and years – and he gives a very persuasive account of his enthusiasms in the face of the narrator’s more sceptical, materialist view of art appreciation. But there are two problems with Theobald’s position. The first is that he has no real creative life force, and the second is that he has been living ‘in denial’ with his plan for the ultimate art work.

His idea for the ideal Madonna has been gestating for two decades, but no fruit has been borne. And this is reflected in his relationship to Serafina. She might have been a virgin-like Madonna (with child) when he first met her, but now she is an old woman. She clearly gets by via her association with ‘visiting gentlemen’ – which is perhaps as close as James could come in the 1870s to implying that she was a prostitute.

What makes the story admirable is the well-sustained pathos of Theobald’s characterisation, and his ultimate tragedy in defeat of an unrealised dream. There is no bitterness or schadenfreude in the story. Mrs Coventry is quite right: Theobald has been telling everybody about his grand scheme, but has produced nothing.

Yet the fact that the narrator follows him into his dream and into his poverty lends a sympathetic pathos to this character sketch of a clearly deluded man. James wrote about artists who could not paint, authors who could not write, great thinkers who could only talk – and yet he was enormously productive himself, for the whole of his fifty year creative life span.

The Madonna of the Future – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Madonna of the Future – eBook formats at Gutenberg

The Madonna of the Future – eBook formats at Gutenberg

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

The Madonna of the Future – plot summary

An un-named outer-narrator relays the account of an inner-narrator (H—) in which he describes a youthful visit to Florence. When viewing the sculptures in the Palazzo Vecchio, he is accosted by Mr Theobald, a man who enthuses about the spirit of the place and its general artistic heritage. He is an American and claims to be an artist with standards so fastidious that he has not sold or kept a single picture.

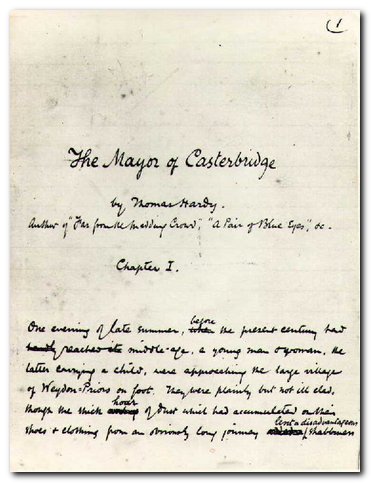

Next day the narrator meets him again in the Uffizi gallery. Theobald continues to rhapsodise about Art, and when they proceed to the Pitti Palace the narrator himself is full of enthusiasm for Raphael’s picture The Madonna of the Chair. Theobald takes an idealist, almost metaphysical view of art criticism, whereas the narrator offers a more materialist interpretation of the picture – that pretty young women were fashionable at the time the portrait was painted. Theobald’s reply to this becomes a prescription for what could be done in the present historical phase. The narrator guesses that he is in fact describing his own aspirations.

The two men meet every day for the next fortnight, and the narrator continues to be astonished by Theobald’s enthusiasm, his knowledge, and his commitment to the world of high Art.

However, Mrs Coventry, a long-time American resident and patronne in Florence informs the narrator that Theobald is a talentless dreamer in whom people have given up believing. He claims to be painting a Madonna which will be a composite of all previous masterpieces of the Italian school.

The narrator invites Theobald to an opera, but he refuses and instead invites the narrator to meet Serafina, the most beautiful woman in Italy, who acts as his model. The narrator is disconcerted to find that she turns out to be an unexceptional and rather stout woman who is no longer young. Theobald reveals that she was an unmarried mother who he rescued and has maintained ever since, following the death of her child. He is also shown Theobald’s portrait sketch of the child, which he admires.

When Theobald asks the narrator his opinion of Serafina, he tells him quite honestly that she is old. This stark honesty shocks Theobald, who realises that he has spent years deceiving himself. The narrator feels slightly guilty for bringing him to this realisation, and encourages him to finish the long-awaited portrait of Serafina as Madonna. Theobald is crestfallen, but vows to finish it in a fortnight.

Theobald then disappears, so the narrator goes back to Serafina’s apartment in order to locate him. She is entertaining another man – who is a vulgar and pretentious artist of trashy objects. Serafina defends Theobald as an honourable friend of twenty years standing, and gives the narrator his address. The other visitor tries to sell the narrator the tasteless statuettes he makes.

When the narrator visits Theobald, he finds him in miserably poor conditions, He is also paralysed with inactivity in front of an empty canvas. He realises that for all his theorising, he has no creative power whatever. The narrator looks after him, but he collapses in a brain fever and dies. After the funeral, the narrator meets Serafina in a church, where she implicitly reveals to him that she is a prostitute.

Principal characters

| I | the un-named outer narrator |

| H— | the inner-narrator |

| Mr Theobald | an American art enthusiast |

| Mrs Coventry | an American patroness of art in Florence |

| Serafina | Theobald’s ideal woman |

| — | an ‘artist’ of kitsch rubbish statuettes |

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

Henry James on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations of James’s novels and stories for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, production features, film reviews, box office, and even quizzes.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The novel is an ironic reversal of the rags to riches story that is normally attached to immigration from the Old World to the New. Karl Rossman manages to go from riches to rags. He starts off with a wealthy and powerful uncle who showers him with luxury, but by the end of the narrative he has nothing, he is searching for work, and he is mixing with criminals and a prostitute. It is worth noting that Karl is not exactly an innocent abroad. He has been expelled from his family home following a sexual dalliance with an older servant woman that resulted in her bearing a child. So although he is only seventeen (or even fifteen) years old, Karl is in fact himself a father.

The novel is an ironic reversal of the rags to riches story that is normally attached to immigration from the Old World to the New. Karl Rossman manages to go from riches to rags. He starts off with a wealthy and powerful uncle who showers him with luxury, but by the end of the narrative he has nothing, he is searching for work, and he is mixing with criminals and a prostitute. It is worth noting that Karl is not exactly an innocent abroad. He has been expelled from his family home following a sexual dalliance with an older servant woman that resulted in her bearing a child. So although he is only seventeen (or even fifteen) years old, Karl is in fact himself a father.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Franz Kafka: Illustrated Life This is a photographic biography that offers an intimate portrait in an attractive format. A lively text is accompanied by over 100 evocative images, many in colour and some previously unpublished. They depict the author’s world – family, friends, and artistic circle in old Prague – together with original book jackets, letters, and other ephemera. This is an excellent starting point for beginners which captures fin de siecle Europe beautifully.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis The Trial

The Trial

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

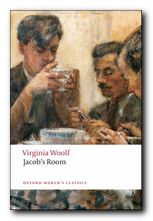

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

The people in Casterbridge believe he is a widower. He himself finds it convenient to believe Susan probably is dead. While travelling to the island of Jersey on business, he falls in love with a young woman named Lucette de Sueur. They have a sexual relationship, and Lucetta’s reputation is ruined by her association with Henchard.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles Jude the Obscure

Jude the Obscure Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales