tutorial, commentary, study resources, web links

Gobseck (1830) is a powerful novella that features a character who crops up in several novels of Balzac’s Comedie Humaine. Jean-Esther van Gobseck is an amazing Scrooge-like character who has reduced his entire life to the acquisition of wealth. He is also a miser who lives in a state of extreme frugality. The story also includes characters who appear later in the later novel Old Goriot (1834), including Anastasia de Resaud, a glamorous socialite who is prepared to rob her own husband to pay off her lover’s gambling debts.

Gobseck – background

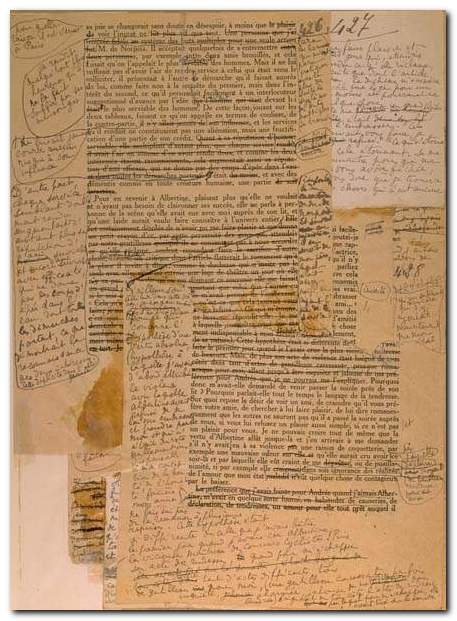

Gobseck is a short novella that first appeared as a newspaper serial in 1830 under the title L’Usurier. It was then published in the periodical Le Voleur later the same year, and after that as a single volume with the title Les Dangers de l’inconduite. It was given its definitive title of Gobseck when it appeared in the definitive Furne edition of La Comedie Humaine in 1842.

All of these separate publications illustrate Balzac’s commercial enterprise in exploiting the potential value of his work, recycling the same materials in so many different formats. He was a great novelist, but there was nothing precious or dilettante in his approach to literature He was a professional writer of immense energy and practical application. He wrote with high literary ideals, but he also wrote to make money. In fact he was usually paying off debts incurred through his extravagant lifestyle and business ventures that had gone wrong. As the French critic Hyppolyte Taine observed ‘the most complete description of Balzac is that he was a man of business – a man of business in debt’.

Gobseck – critical commentary

Gobseck is is essentially a a study in extreme avarice. The principal character is a money-lender who charges exorbitant interest rates. He is also a business speculator who who strikes crooked deals with collaborators and even rivals. The foundation of his wealth is in colonial exploitation of the Dutch East Indes. He is also a collector, and a hoarder of precious objects. Most importantly, he has reduced his personal morality to two principles – the relentless pursuit of self-interest, and the worship of gold.

Throughout the story he appears to be consistent in his methods and the successful application of his principles. But the conclusion of the story reveals the ultimate futility of his enterprise. The house he lives in is packed with foodstuffs that have gone rotten whilst he has been haggling over their selling price. As for his gold and other material assets, he has absolutely no one – no friends, neighbours, or relations – to whom he can bequeath them. He neither uses nor enjoys the artefacts he has collected. His obsession is ultimately reductive. He stands alongside Felix Grandet, the avaricious father in Eugene Grandet (1833) as one of the great and tragic misers of Balzac’s fiction.

And yet …

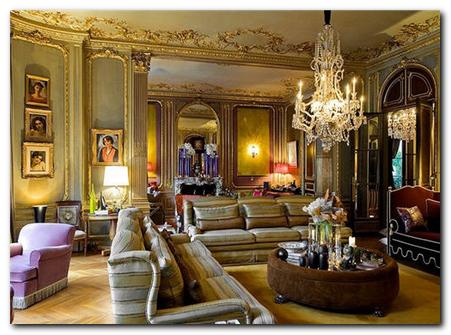

Gobseck is supposed to be an emotionless puritan with no interests except self-interest and the relentless acquisition of money. Yet his descriptions of his creditors and their domestic interiors are those of an aesthete. He knows the names of furnishings, fabrics, and the details of decorative wood inlays, It is difficult to escape the suspicion that these reflect the interests of Balzac himself, who was a great enthusiast for sumptuous interior décor.

He [Balzac] was a profound connoisseur in these matters; he had a passion for bric-à-brac, and his tables and chairs are always in character.

This observation by implication criticises Balzac of failing to make a distinction between his own interests and those of his fictional character. It is certainly true that Balzac intrudes his own political and religious beliefs, his opinions and manifestos on taste with prodigious vitality throughout his fictional work

There is also an argument that he puts a lot of himself into his fictional characters – as do many novelists in their work. In addition to this, it should also be kept in mind that there can be unacknowledged contradictions between an author’s conscious and unconscious intentions. In other words, Balzac is creating a character (Gobseck) whom he is offering as a negative example of greed and excessive puritanism – but he cannot resist giving this character a knowledge and appreciation of furniture, interior décor, and fine arts that Balzac posessed himself.

Is it a novella?

There is good reason for considering Gobseck as an extended character sketch sandwiched into a short story. The basic structure of the tale is the issue of Camille de Grandlieu and her infatuation with Ernest de Restaud. Her mother thinks Restaud is not a suitable marriage prospect because he lacks money. This issue is resolved by the family lawyer Derville, whose largely first-person account terminates with the information that Restaud has inherited generously, and will therefore be acceptable.

But his explanation involves the potted life history of Gobseck, plus his complex financial dealings with the Restaud family. This notably includes his relationship with Anastasia, who tries to pawn her family’s diamonds in order to raise money to pay off the gambling debts of her lover, the playboy Maxime de Trailles.

This episode not only has the substance of a literary form longer than the short story, but it also forms part of a larger literary work – Old Goriot. Anastasia is the elder daughter of Father Goriot, a man who has been brought to the point of ruin by his two spendthrift and morally bankrupt daughters.

The most convincing reason for considering Gobseck as a novella is that it has as its controlling symbol and metaphor that of avarice. This is Gobseck’s raison d’etre, and it dictates all his actions from the start of the narrative up to its quasi-tragic conclusion. But other characters are also tainted by their relationship to money. Madame de Grandlieu would not dream of letting her daughter marry a young man unless he was rich. Anastasia de Restaud is up to her ears in debt. She has fleeced her own father and still needs more money to pay off de Trailles’ gambling debts.

Money runs through all aspects of the story like the letters in a stick of rock. It is a theme, a metaphor, and a symbol all in one. And that is one of the constituents of a novella – that it has unifying elements holding all its parts together.

La Comedie Humaine

From 1834 onward Balzac conceived of his novels as free-standing but interlocking elements in a huge study of French society to which he gave the general title of La Comedie Humaine. He used the device of recurring characters and overlapping events to produce a sort of three-dimensional literary portrait of post-revolutionary France.

Gobseck is a very good example of how this method works. The rapacious and eponymous money-lender is the central figure in this novella, but he crops up in a number of the other works as a minor character – in Old Goriot (1834), Cesar Birotteau (1837), and The Unconscious Comedians (1846).

But more importantly, the dramatic incident of lending money to Anastasia de Restaud to pay off her lover’s gambling debts also forms part of the plot of Old Goriot. Anastasia is the elder daughter of Goriot, who is a doting father. She and her sister Delphine have brought about his financial ruin by the demands they have made on his good nature. We thus have a more fully-rounded portrait of her selfish and self-indulgent nature than from one novel alone.

We also know that even after being rescued from her financial problems by borrowing yet more money from Eugene de Rastignac (another recurring figure) she cannot be bothered to go to her own father’s funeral.

If you wish to track any of the characters and their appearances in Balzac’s whole oeuvre, there is a huge list on line with detailed biographies at – The Repertory of the Comedy Humaine

Gobseck – study resources

Gobseck – Paperback – Amazon UK

Gobseck – Paperback – Amazon US

Balzac – Complete Works – Kindle – Amazon UK

Balzac – Complete Works – Kindle – Amazon US

Cambridge Companion to Balzac – Cambridge UP – Amazon UK

Gobseck – plot summary

Young Camille de Grandlieu has an enthusiasm for Ernest de Restaud, but her mother thinks he has not enough money to get married. The family lawyer Derville recounts the history of a money-lender Jean-Esther van Gobseck – from his earliest days as a Dutch imperialist adventurer to his later years as a desiccated and miserly usurer.

Gobseck believes that the only worthwhile values are self-interest and the worship of gold. He describes a morning recovering debts from clients. The first is aristocratic Anastasia de Restaud and the second is a poor seamstress Fanny Malvaut. He considers his influence over those who have fallen into debt as a form of power. He is also part of a usurer’s cabal that meets weekly to share information.

Derville buys the practice where he works with a loan from Gobseck. He pays off the debt in five years and marries Fanny Malvaut. He attends a bachelors’ breakfast banquet where he meets the dandy Maxime de Trailles who is in need of money to pay off gambling debts. Anastasia de Restaud (his lover) offers her family diamonds as security on a loan. Gobseck strikes a murky deal that includes bills of credit in de Trailles’ name which he has bought cheaply from another money-lender. Restaud then calls, demanding the return of his family’s jewels. He is forced to enter a legal agreement drawn up by Derville.

Restaud visits Derville to arrange papers relating to his will and a false sale of his property. He leaves his younger children out of his will, since he believes they may not be his own offspring. Restaud then falls ill and dies in conflict with his wife. She burns a secret counter-document to his will. Gobseck arrives and immediately takes possession of the house, which now belongs to him. He lives in the house and becomes a government liquidator for Haiti and San Domingo.

He appoints Derville his executor, who on searching the house following Gobseck’s death finds it packed with trinkets, gifts, antiques, and foodstuffs that had turned rotten because he had been haggling so long over the price. Ernest de Restaud inherits enough money to enable him to marry Camille.

Gobseck – principal characters

| Madame de Grandlieu | an aristocratic grande dame |

| Camille de Grandlieu | her young daughter, in love with Ernest de Restaud |

| Maitre Derville | lawyer to the Grandlieu family, neighbour of Gobseck |

| Jean-Esther van Gobseck | a Dutch Jewish miser and money leander |

| Anastasia de Restaud | an improvident and adulterous wife |

| Ernest de Restaud | her only legitimate son, who marries Camille |

© Roy Johnson 2017

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

During Christmas dinner, whilst Pip is scared that someone will notice the missing pie. Police officers arrive and hunt through the marshes outside the village for escaped convicts. They accost the man helped by Pip, but when questioned about where he got the food and file, he claims he stole the items himself. The police take him off to the Hulk, a giant prison ship.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory.

The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens contains fourteen essays which cover the whole range of Dickens’s writing, from Sketches by Boz through to The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Some address important thematic topics: childhood, the city, and domestic ideology. Others consider the serial publication and Dickens’s distinctive use of language. Three final chapters examine Dickens in relation to work in other media: illustration, theatre, and film. The volume as a whole offers a valuable introduction to Dickens for students and general readers, as well as fresh insights, informed by recent critical theory. Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Maisie Knew

What Maisie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors The Golden Bowl

The Golden Bowl The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All the essays in this compilation are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James is intended to provide a critical introduction to James’ work. Throughout the major critical shifts of the past fifty years, and despite suspicions of the traditional high literary culture that was James’ milieu, as a writer he has retained a powerful hold on readers and critics alike. All the essays in this compilation are written at a level free from technical jargon, designed to promote accessibility to the study of James and his work.

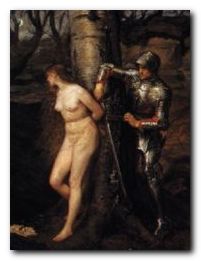

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

Marlowe’s description of the stained glass window reinforces his characterisation. He describes the figures in a naive manner, as if he had never seen such an emblematic composition before. The lady ‘didn’t have any clothes on’ and the knight has pushed his visor back ‘to be sociable’ but he was ‘not getting anywhere’. Raymond Chandler is simultaneously creating his main character – who is tough, but a little naive – and is giving us clues about how we should view the novel. It’s not to be taken entirely seriously. In fact describing European art from a naive American perspective is a device he has taken from Mark Twain. There is lots of serious crime ahead in the rest of the novel, but he is creating a witty and ironic point of view which we are invited to share.

The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

The Cambridge Companion to Proust

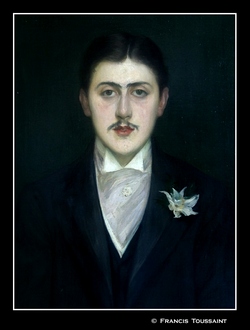

The Cambridge Companion to Proust Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust