tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

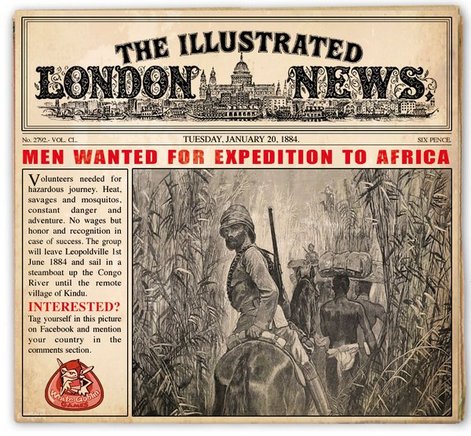

The Well-Beloved was first serialized in the London Illustrated News in 1892. It was then published as a complete novel in 1897 by Osgood, McIlvaine & Co. The full title was originally The Pursuit of the Well-Beloved: A Sketch of a Temperament, which emphasises the protagonist’s fixation on the ‘ideal woman’.

The Well-Beloved – critical commentary

Sex in the novel

Despite all Jocelyn’s romantic idealism and his incontinent fixations on younger and younger women, he actually spends the whole novel with no sexually consummated adult relations at all.

This is strange, because the events of the narrative begin with a typically Hardyesque appeal to old folk traditions of pre-marital sex. Jocelyn arranges to meet the first Avice at night in the castle, presumably with a view to taking advantage of this tradition. But she sends him a note canceling the rendezvous specifically on the grounds that she does not agree to the idea – which certainly confirms that she was conscious of this being the reason for their nocturnal meeting.

Jocelyn goes off instead with Marcia, a woman who just happens to be walking past at the time, and he proposes marriage to her as soon as they reach London. It’s true that he spends a few days in a hotel with Marcia when he is supposed to be arranging their marriage. This would have been unthinkable in his native environment, but could pass in the more socially advanced mores of the capital. Yet there is nothing in the text to suggest that they enjoy a sexual relationship.

Just as he thinks he is going to secure the second Avice, she reveals that she is already married to someone else, and there is a suggestion that as a couple they have taken advantage of the island custom, which rubs salt into Jocelyn’s emotional wound at the time.

The same happens with the third Avice, who when confronted by his offer of marriage, runs off with someone else of her own age. Jocelyn thus spends the whole novel (forty years plus) pursuing phantoms. It is to presumably part of Hardy’s purpose to reveal this emotional absurdity. Then in the end Jocelyn settles for a marriage of convenience with his old friend Marcia Bencomb in a union which he rather tastelessly points out to her is based on friendship and certainly not love.

Hardy explored the consequences of sexual desire and activity in many of his novels (as frankly as was permitted at the time) most notably in Jude the Obscure which he wrote only a few years later in 1895. But The Well-Beloved appears to explore nothing more than the futility of pursuing idealised concepts of the opposite sex, which Jocelyn does – three times over.

The result of Jocelyn’s experiences might be thought as Hardy’s warning against romantic idealization – yet there is very little evidence in the text to support this idea. Jocelyn’s life trajectory is not held up as a failure or an example of emotional under-development. He is simply driven by this impulse until his last attempt fails and he is prepared to settle for a sexless relationship based on an old friendship.

Readers embarking on psychological interpretations of novels and their authors might like to keep in mind that not long after the publication of The Well-Beloved Thomas Hardy married a woman (Florence Dugdale) who was forty years younger than him – possibly an instance of what Oscar Wilde claimed was ‘life imitating art’?

Social background

The practical working background of the novel is sensitively observed. Just as every aspect of woodcutting and the timber business informs The Woodlanders, and agriculture permeates Tess of the d’Urbervilles, here in The Well–Beloved the stone industries of Portland are carefully incorporated. The business of mining and cutting stone is the enterprise on which the Bencomb and Pierston businesses were founded, and Hardy pointedly reminds us in one part of the story that the local stone was used to build St Paul’s cathedral.

This is Hardy the son of a stonemason and himself an architectural designer underscoring the commercial life of Wessex out of which these lives have emerged. It is unfortunate that the fictional integration of the commerce and the business dynasties are not so well incorporated as they are in the other novels. They do not form essential parts of the narrative in the same way as the destinies of Giles Winterbourne and Tess are determined by their occupations in the rural industries in which they participate.

Moreover, Jocelyn rises to fame as a sculptor, a shaper of this local stone – but without any credible evidence of his artistic talents or activity. None of his work is discussed, and the twenty year periods between each version of Avice are skipped over without comment. This reinforces the idea that all Hardy’s attention was focused onto Jocelyn’s obsession with his ideal woman, and it contributes to the overwhelming sense of weakness in The Well-Beloved compared with his other great novels.

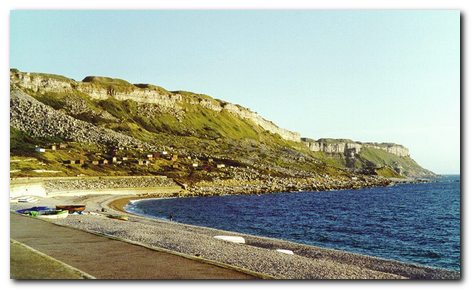

The Isle of Slingers

Hardy chose to re-name the location of the novel, as he did in so many of his other works. But ‘The Isle of Slingers’ is actually an old name for Portland Island – given to it because of the habit of the local population to hurl stones at unwanted visitors – or ‘kimberlins’ or ‘foreigners from the mainland of Wessex’ as they are called in the text.

The total population of the island around that time was only about eighty households, which coupled with the xenophobia enshrined in its popular name, resulted in a great deal of inter-marriage and the fact that everybody knew everybody else’s business. These social factors are well reflected in the novel .

Avice Caro marries a cousin (which was legally controversial at the time); all three generations of women have the same first name (Avice); and the grand-daughter eventually marries someone with the surname Pierston – which is that of the protagonist, Jocelyn.

The three Avices, the second something like the first, the third a glorification of the first, at all events externally, were the outcome of the immemorial island customs of intermarriage and prenuptial union, under which conditions the type of feature was almost uniform from parent to child through generations.

The Well-Beloved – Study resources

![]() The Well-Beloved – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

The Well-Beloved – Penguin Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Well-Beloved – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

The Well-Beloved – Penguin Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Well-Beloved – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

The Well-Beloved – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Well-Beloved – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

The Well-Beloved – Wordsworth Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

The Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle eBook

![]() The Well-Beloved – eBooks at Project Gutenberg

The Well-Beloved – eBooks at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Well-Beloved – audiobook at LibriVox.org

The Well-Beloved – audiobook at LibriVox.org

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

Authors in Context – Thomas Hardy – Amazon UK

![]() Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

Oxford Reader’s Companion to Hardy – Amazon UK

The Well-Beloved – plot summary

Part First

Chapter I. Would-be sculptor Jocelyn Pierston returns to his native Isle of Slingers [Isle of Portland] in Dorset to visit his father after three years living in London. He is greeted enthusiastically with a kiss by his childhood friend Avice Caro.

Chapter II. Jocelyn reassures the embarrassed Avice, and proposes marriage to her, then immediately regrets it. He has a romantically idealised image of Woman which is constantly shifting from one object to another. Avice has become a cultivated woman, and after a month’s sojourn they are understood to be engaged.

Chapter III. At the end of his holiday Jocelyn goes to meet Avice at night to say farewell, but she does not show up at the appointed place.

Chapter IV. She sends him a note excusing herself because she does not approve of the local tradition of pre-marital sex. He leaves nevertheless and meets Marcia Bencomb, who is running away from home and her father, who is a rival to Jocelyn’s father in the stone quarrying trade.

Chapter V. Jocelyn and Marcia shelter from a sudden storm under a boat, then they are forced to stay overnight at a hotel in Budmouth.

Chapter VI. They travel together to London where, having decided that Marcia is the latest incarnation of his ideal woman, Jocelyn asks her to marry him. They book into a hotel, and he goes to make the necessary marriage arrangements, then visits his friend Somers who is a painter.

Chapter VII. Jocelyn explains to Somers his personal theory of the idealised woman, up to his recent experiences with Avice and Marcia. He rationalises his fickleness, them temporises with Marcia regarding the marriage arrangements.

Chapter VIII. Jocelyn and Marcia squabble over their uncertain social status. She writes to her father, who refuses to endorse her proposed marriage on grounds of rivalry between the two families. Marcia leaves the hotel, and is subsequently taken back home by her father. Jocelyn later hears that Avice has married a cousin and that Marcia is to go on a world tour with her father.

Chapter IX. The years pass. Jocelyn becomes a successful sculptor, but he continues to flit from one example of his idealised woman to another.

‘The Isle of Slingers’

Part Second

Chapter I. When Jocelyn is middle-aged his father dies, leaving him quite wealthy. He attends a fashionable party, still in search of his ideal woman, and thinks he might have found her in the form of Mrs Nicola Pine-Avon, an intellectual widow.

Chapter II. But when he visits Mrs Pine-Avon he finds her rather remote, so he insults her and leaves. At another social event he reads a letter telling him that Avice has died.

Chapter III. This news inflames his old feelings for Avice, who he now realises he has undervalued, and he bitterly regrets the loss. He goes back to the island in time to see her buried in the local churchyard.

Chapter IV. He meets Avice’s daughter Ann, whose family fell on hard times, leaving her to work as a laundress. Jocelyn thinks of her as the reincarnation of her mother; he calls her by her mother’s name; and wishes he could live locally and pay court to her.

Chapter V. Back in London he meets Avice (Ann) at the docks and feels powerfully attracted to her, even though she is only a laundress. He decides to rent a manor-house on the island so as to be near her.

Chapter VI. He arranges for Avice to visit his house daily to do his laundry. He thinks of her as the original Avice – and realises that he is hopelessly in thrall to a woman who he ‘despises’ intellectually.

Chapter VII. Jocelyn pursues Avice in her daily life on the island. She reveals her knowledge of her mother’s sad history (deserted by her intended) and even though she seems indifferent to him, Jocelyn decides he wants to marry her.

Chapter VIII. When he next confronts her she reveals that she rapidly tires of men after first finding them attractive. But he still intends to pursue his plans.

Chapter IX. Jocelyn is jealously watching Avice take washing to a soldier-lover when his friend Somers suddenly arrives. Jocelyn admits he is completely in thrall to Avice. He is then visited by Mrs Pine-Avon, who pays court to him, but he is completely consumed by his current obsession.

Chapter X. Somers sees Mrs Pine-Avon and wants to marry her. Avice is upset about something, and Jocelyn offers to take her on as a temporary help in London.

Chapter XI. When they get there his housekeepers have drunk his wine and absconded. Avice keeps herself separate from him, even though he feels completely responsible for her welfare.

Chapter XII. Eventually he asks her to marry him. She refuses, revealing that she has already married Isaac Pierston, with whom she has quarrelled and separated. Jocelyn reveals his former relationship with her mother, and he takes Avice back to the island.

Chapter XIII. Isaac is brought back and reconciled with his wife, who then has a baby she christens Avice. Jocelyn goes back to London, where Somers is due to marry Mrs Pine-Avon.

‘The Isle of Slingers’

Part Third

Chapter I. Twenty years later Jocelyn is in Rome, having sent Avice money from time to time. He receives a letter from her telling of her husband’s death, and he decides to visit the island. She is living in his old house, and he immediately entertains the idea of marrying her – until he sees her daughter, who he regards as the reincarnation of her grandmother.

Chapter II. Jocelyn has misgivings that the old curse is still upon him. He rescues the young Avice when she is stuck on some rocks and feels that he detects a direct connection running from grandmother to grand-daughter.

Chapter III. He revisits young Avice’s mother and proposes to marry the girl. She agrees to help him in such a plan. They all visit the castle where Jocelyn was supposed to meet young Avice’s grandmother. Avice’s mother encourages her daughter to favour Jocelyn, but the girl is not really interested – and so far she has only ever seen him at night.

Chapter IV. An aged Somers suddenly appears along with his matronly wife (Mrs Pine-Avon) and several children. Jocelyn stays away from young Avice during their visit. Mother Avice falls ill, but she persuades her daughter to accept Jocelyn because he is kind, rich, and upper class. Jocelyn reveals to her his connections with her mother and grandmother – and at the same time he begins to think that the marriage might not be a good idea.

Chapter V. Jocelyn takes Avice and her mother to his new house and studio In London, but Avice is still not enthusiastic about him. He goes back to the island on what is supposed to be the eve of his wedding day.

Chapter VI. Mother Avice is ill, but glad to have her plans for her daughter’s wedding almost fulfilled. However, young Avice elopes with young Henri Leverre the same night, and her mother dies with the shock of events.

Chapter VII. Marcia Bencomb (Leverre’s stepmother) arrives [after forty years] to seek out Jocelyn via the odd connection between them. Jocelyn accepts what has happened, and promises to settle a handsome dowry on young Avice.

Chapter VIII. Mother Avice is buried, then Jocelyn falls ill, after which he loses his interest in aesthetics. Marcia nurses him, and reveals herself as the older woman she now is. They move back to the island and eventually get married (as old friends, not lovers). Jocelyn devotes himself to improving local living conditions.

Hardy’s WESSEX

The Well-Beloved – principal characters

| Jocelyn Pierston | a young would-be sculptor |

| Avice Caro | his childhood friend |

| Mrs Caro | a widow, her mother |

| Marcia Bencomb | daughter of rival family to Pierstons |

| Alfred Somers | Jocelyn’s friend, a painter |

| Mrs Nicola Pine-Avon | a young intellectual widow |

| Ann Avice Caro | Avice’s daughter, a laundress |

| Avice Pierston | Avice Caro’s daughter, a governess |

Hardy’s study

reconstructed in Dorchester museum

Further reading

![]() John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

John Bayley, An Essay on Hardy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

![]() Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

Penny Boumelha, Thomas Hardy and Women: Sexual Ideology and Narrative Form, Brighton: Harvester, 1982.

![]() Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

Kristin Brady, The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1982.

![]() L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

L. St.J. Butler, Alternative Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1989.

![]() Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

Raymond Chapman, The Language of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1990.

![]() R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

R.G.Cox, Thomas Hardy: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

![]() Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

Ralph W.V. Elliot, Thomas Hardy’s English, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984.

![]() James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

James Gibson (ed), The Complete Poems of Thomas Hardy, London, 1976.

![]() Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

Florence Emily Hardy, The Life of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan, 1962. (This is more or less Hardy’ s autobiography, since he told his wife what to write.)

![]() P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

P. Ingham, Thomas Hardy: A Feminist Reading, Brighton: Harvester, 1989.

![]() P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

P.Ingham, The Language of Class and Gender: Transformation in the English Novel, London: Routledge, 1995,

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, London: Bodley Head, 1971.

![]() Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006. (This is the definitive biography.)

![]() Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

Michael Millgate and Richard L. Purdy (eds), The Collected Letters of Thomas Hardy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978-

![]() R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

R. Morgan, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge, 1988.

![]() Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

Harold Orel (ed), Thomas Hardy’s Personal Writings, London, 1967.

![]() F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

F.B. Pinion, A Thomas Hardy Companion, London: Macmillan, 1968.

![]() Norman Page, Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

Norman Page, Thomas Hardy, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1977.

![]() Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

Rosemary Sumner, Thomas Hardy: Psychological Novelist, London: Macmillan, 1981.

![]() Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

Richard H. Taylor, The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy, London, 1978.

![]() Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

Merryn Williams, A Preface to Hardy, London: Longman, 1976.

Other works by Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is probably the most popular of Hardy’s late, great novels. The sub-title is ‘A Pure Woman’, and it is a story which explores the tragic consequences of a young milkmaid who becomes the victim of the men she encounters. First she falls for the spiritual but flawed Angel Clare, and then the physical but limited Alec Durberville takes advantage of her. This novel has some of the most beautiful and the most harrowing depictions of rural working conditions which reveal Hardy as a passionate advocate for those who work the land. It also has a wonderfully symbolic climax at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. There is poetry in almost every page.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

The Woodlanders (1887) Giles Winterbourne, an honest woodsman, suffers with the many tribulations of his selfless love for Grace Melbury, a woman above his station in this classic tale of the West Country. She marries the new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, but leaves him when she learns he has been unfaithful. She turns instead to Giles, who nobly allows her to sleep in his house during stormy weather, whilst he sleeps outside and brings on his own death. It’s often said that the hero of this novel is the woods themselves – so deeply moving is Hardy’s account of the timbered countryside which provides the backdrop for another human tragedy and a study of rural life in transition.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

Wessex Tales Don’t miss the skills of Hardy as a writer of shorter fictions. None of his short stories are really short, but they are beautifully crafted. This is the first volume of his tales in which he was seeking to record the customs, superstitions, and beliefs of old Wessex before they were lost to living memory. Yet whilst dealing with traditional beliefs, they also explore very modern concerns of difficult and often thwarted human passions which he developed more extensively in his longer works.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Thomas Hardy – web links

Thomas Hardy at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major novels, book reviews. bibliographies, critiques of the shorter fiction, and web links.

The Thomas Hardy Collection

The complete novels, stories, and poetry – Kindle eBook single file download for £1.29 at Amazon.

Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

Thomas Hardy at Wikipedia

Biographical notes, social background, the novels and literary themes, poetry, religious beliefs and influence, biographies and criticism.

The Thomas Hardy Society

Dorset-based site featuring educational activities, a biennial conference, a journal (three times a year) with links to the texts of all the major works.

The Thomas Hardy Association

American-based site with photos and academic resources. Be prepared to search and drill down to reach the more useful materials.

Thomas Hardy on the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors, actors, production features, box office, film reviews, and even quizzes.

Thomas Hardy – online literary criticism

Small collection of academic papers and articles ‘favoring signed articles by recognized scholars and articles published in peer-reviewed sources’.

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex

Evolution of Wessex, contemporary reviews, maps, bibliography, links to other web sites, and history.

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Thomas Hardy

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Collected Stories

Collected Stories Picasso said ‘I paint forms as I think of them, not as I see them’ which resulted in objects and sitters portrayed in a fragmented manner, from a number of different perspectives, in a series of overlapping planes – all of which the viewer is invited to recompose mentally to form a three-dimensional image, rendered on a two dimensional surface (though there were also a few cubist sculptures).

Picasso said ‘I paint forms as I think of them, not as I see them’ which resulted in objects and sitters portrayed in a fragmented manner, from a number of different perspectives, in a series of overlapping planes – all of which the viewer is invited to recompose mentally to form a three-dimensional image, rendered on a two dimensional surface (though there were also a few cubist sculptures). In her study of this subject Sarah Latham Phillips offers a detailed reading of

In her study of this subject Sarah Latham Phillips offers a detailed reading of

Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth