conjugal life a la Bloomsbury

Nigel Nicolson is the son of writer Vita Sackville-West and diplomat-politician Harold Nicolson. When his parents died he found a locked leather Gladstone bag in his mother’s study, cut it open, and discovered a diary containing an autobiographical account of her affair with Violet Trefusis. Portrait of a Marriage is made up of these diary entries, interspersed with his own explanations of what went on in those parts of the story his mother doesn’t cover.

It’s not really a portrait of a marriage at all until the final chapter. Harold Nicolson remains a vaporous non-presence throughout, and there is almost nothing about the relationship between them except for her protestations at ‘depending’ on him. The central issue is her passionate three-year fling that has her dressing up as a man, leaving her husband and children behind to ‘elope’ to France, and to live in Monte Carlo, gambling at the tables with money they didn’t have, whilst Trefusis was debating the wisdom of marrying her fiancé Denys, whom she didn’t love or desire.

It’s not really a portrait of a marriage at all until the final chapter. Harold Nicolson remains a vaporous non-presence throughout, and there is almost nothing about the relationship between them except for her protestations at ‘depending’ on him. The central issue is her passionate three-year fling that has her dressing up as a man, leaving her husband and children behind to ‘elope’ to France, and to live in Monte Carlo, gambling at the tables with money they didn’t have, whilst Trefusis was debating the wisdom of marrying her fiancé Denys, whom she didn’t love or desire.

It’s an amazing story, and most instructive in class terms. Husbands colluding with their wives’ lovers for the sake of money to keep estates solvent, whilst paternity suits raged to the tune of £40,000 (this in the 1900s).

I was also very struck by how much of Sackville-West’s literary style is similar to Virginia Woolf’s. She is a great fan of the stream of immediate memory, and a narrative couched in extended metaphors and rhapsodic interludes. There are lots of schooners breasting silvery waves with the wind full in their sails, and that sort of thing.

There’s nothing here that will be remotely shocking in the sexual sense to modern readers. ‘I had her’ is about as explicit as it gets. But the behaviour – duplicitous, self-seeking, naive, and hypocritical – is breathtaking. Vita Sackville West finally broke off the relationship with Trefusis because she thought she might have had some sexual connection with Denys Trefusis – the man she had recently married – whilst West had two children with Harold Nicolson. Actually, Violet Trefusis hadn’t had any such connection, having made it a condition of her marriage contract.

There’s a lot of utterly snobbish ancestor-worship to get through and Nicolson’s chapters are written in a creakingly old-fashioned manner: ‘She permitted him liberties but not licence’. In fact Nicolson fils seems as wrapped up in snobbery as his mother:

her real friends were souls, but real souls who had some breeding and a gun, who could make a fourth at bridge, and who knew the difference between claret and burgundy

I found it quite hard to keep my rage down when reading of the almost unbelievable concern for money, status, and class. The events are only just over a hundred years ago, and this account of them was written in the 1970s, but it was like reading about social dinosaurs.

The latter part of the book outlines West’s affairs with Geoffrey Scott and Virginia Woolf – both of which she recounted in detail to her husband. Their son makes the case that the bond between them was strong enough to outlast these affairs – which it did, though on the basis that they had no sexual relationship with each other.

Of course you don’t need a brass plaque on your door to realise why a child would want to portray his bisexual and adulterous parents in the best possible light, but I must say all this is sometimes difficult to accept calmly.

As time went on the affairs petered out and the Nicolsons settled down to a quieter life, the major part of which they spent separately – he in London, she in their house at Sissinghurst – which might account for the longevity of the union.

These were people who seemed to have separated out sex from marriage, who obviously cared for each other, and yet spent most of their time apart, writing endless letters saying how much they missed each other. They also made sure their children were kept out of the way at all times. Maybe there’s a lesson in there somewhere?

However, there is one very good thing to say for this memoir-cum-history. Anyone who wants a vivid, living example of the social values and the bohemian behaviour of the Bloomsbury Group need look no further. It’s all here.

© Roy Johnson 2004

Nigel Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, London: Orion Books, 2004, pp.216, ISBN: 1857990609

More on Harold Nicolson

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Twentieth century literature

More on Vita Sackville-West

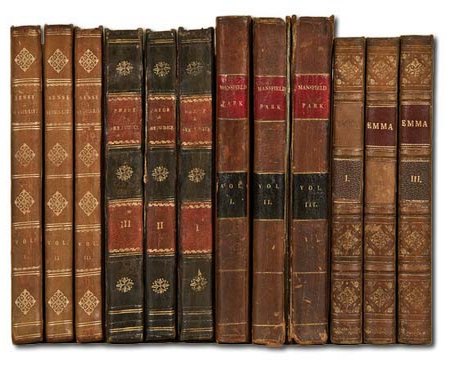

Sense and Sensibility (1811) casts two young and marriageable sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood as representatives of ‘sense’ and ‘sensibility’ respectively. Elinor bears her social disappointments with dignity and restraint – and thereby gets her man. Marianne on the other hand is excitable and impetuous, following her lover to London – where she quickly becomes disillusioned with him. Recovering and gaining more ‘sense’, she then finally sees the good qualities in her old friend Colonel Brandon, who has been waiting in the wings and is now conveniently on hand to propose marriage.

Sense and Sensibility (1811) casts two young and marriageable sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood as representatives of ‘sense’ and ‘sensibility’ respectively. Elinor bears her social disappointments with dignity and restraint – and thereby gets her man. Marianne on the other hand is excitable and impetuous, following her lover to London – where she quickly becomes disillusioned with him. Recovering and gaining more ‘sense’, she then finally sees the good qualities in her old friend Colonel Brandon, who has been waiting in the wings and is now conveniently on hand to propose marriage. Northanger Abbey (1818) opens in the drawing rooms of Bath. The heroine is imaginative Catherine Morland who falls in love with Henry Tilney, a young clergyman. When he invites her to meet his family at the Abbey however, she sees nothing but Gothic melodrama at every turn – since they were very fashionable at the time. Her visions of medieval horror prove groundless of course. This is Jane Austen’s satirical critique of Romantic cliché and excess. But Catherine eventually learns to see the world in a realistic light – and gets her man in the end. This volume also contains the early short novels Lady Susan and The Watsons, as well as the unfinished Sanditon.

Northanger Abbey (1818) opens in the drawing rooms of Bath. The heroine is imaginative Catherine Morland who falls in love with Henry Tilney, a young clergyman. When he invites her to meet his family at the Abbey however, she sees nothing but Gothic melodrama at every turn – since they were very fashionable at the time. Her visions of medieval horror prove groundless of course. This is Jane Austen’s satirical critique of Romantic cliché and excess. But Catherine eventually learns to see the world in a realistic light – and gets her man in the end. This volume also contains the early short novels Lady Susan and The Watsons, as well as the unfinished Sanditon. Mansfield Park (1814) is more serious after the comedy of the earlier novels. Heroine Fanny Price is adopted into the family of her rich relatives. She is long-suffering and passive to a point which makes her almost unappealing – but her refusal to tolerate any drop in moral standards eventually teaches lessons to all concerned. (All that is except standout character Mrs Norris who is a sponging and interfering Aunt you will never forget.) The hero Edmund is dazzled by sexually attractive Mary Crawford – but in the nick of time sees the error of his ways and marries Fanny instead. Slow moving, but full of moral subtleties.

Mansfield Park (1814) is more serious after the comedy of the earlier novels. Heroine Fanny Price is adopted into the family of her rich relatives. She is long-suffering and passive to a point which makes her almost unappealing – but her refusal to tolerate any drop in moral standards eventually teaches lessons to all concerned. (All that is except standout character Mrs Norris who is a sponging and interfering Aunt you will never forget.) The hero Edmund is dazzled by sexually attractive Mary Crawford – but in the nick of time sees the error of his ways and marries Fanny instead. Slow moving, but full of moral subtleties. Emma (1816) Charming and wilful Emma Woodhouse amuses herself by dabbling in other people’s affairs, planning their lives the way she sees fit. Most of her match-making plots go badly awry, and moral confusion reigns until she abandons her self-delusion and wakes up to the fact that stern but honourable Mr Knightly is the right man for her after all. As usual, money and social class underpin everything. Some wonderful comic scenes, and a rakish character Frank Churchill who finally reveals his flaws by making the journey to London just to get his hair cut.

Emma (1816) Charming and wilful Emma Woodhouse amuses herself by dabbling in other people’s affairs, planning their lives the way she sees fit. Most of her match-making plots go badly awry, and moral confusion reigns until she abandons her self-delusion and wakes up to the fact that stern but honourable Mr Knightly is the right man for her after all. As usual, money and social class underpin everything. Some wonderful comic scenes, and a rakish character Frank Churchill who finally reveals his flaws by making the journey to London just to get his hair cut. Persuasion (1818) is the most mature of her novels, if one of the least exciting. Heroine Anne Elliott has been engaged to Captain Wentworth, but has broken off the engagement in deference to family and friends. Meeting him again eight years later, she goes against conventional wisdom and accepts his second proposal of marriage. Anne is a sensitive and thoughtful character, quite unlike some of the earlier heroines. Jane Austen wrote of her “She is almost too good for me”. There is a shift of location to Lyme Regis for this novel, which reveals for the first time a heroine acting from a deep sense of personal conviction, against the grain of conventional wisdom.

Persuasion (1818) is the most mature of her novels, if one of the least exciting. Heroine Anne Elliott has been engaged to Captain Wentworth, but has broken off the engagement in deference to family and friends. Meeting him again eight years later, she goes against conventional wisdom and accepts his second proposal of marriage. Anne is a sensitive and thoughtful character, quite unlike some of the earlier heroines. Jane Austen wrote of her “She is almost too good for me”. There is a shift of location to Lyme Regis for this novel, which reveals for the first time a heroine acting from a deep sense of personal conviction, against the grain of conventional wisdom.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.