tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

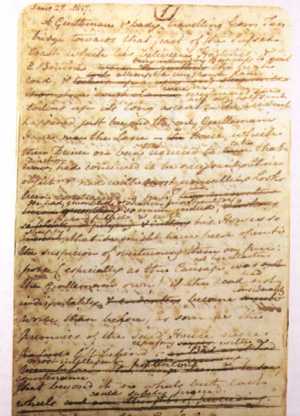

Poor Richard first appeared in The Atlantic Monthly magazine over three issues in June—August 1867. Its next appearance in book form was as part of the collection Stories Revived published in London by Macmillan 1885. This is the one of four stories James wrote with the American Civil War as a background. The other stories are The Story of a Year (1865), A Most Extraordinary Case (1868), and The Romance of Certain Old Clothes (1868).

The American Civil War – 1861-1865

Poor Richard – critical commentary

The title

The term Poor Richard is taken from a famous American publication, Poor Richard’s Almanack which was written and published each year in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin between 1732 and 1758. It was a very popular compilation of weather forecasts, practical household hints, and puzzles, and was padded out with aphorisms and proverbs related to thrift, industry, and frugality. Hence the link to Richard Maule’s progress via work, abstinence, and honesty.

Interpretation

It is difficult to see this story as anything but a warning against the fickleness of women. Gertrude ‘encourages’ Richard; she is in love with Captain Severn; and when Severn is killed in the war she is prepared to marry Major Lutterel, even though she does not love him. She is only twenty-four; she is rich, and she’s good-looking. There is no reason for her to accept an offer from a much older man for whom she feels no affection. Lutterel is thirty-six and he has no money.

Another way to see the story is as a short Bildungsroman – a narrative of growth and education into wisdom. Richard starts out as a drunken wastrel, and then propelled by his love for Gertrude manages to give some clarity and purpose to his life. He does not get the girl, but in the end he tells the truth, he sells the farm, does the honourable social thing by joining in the war, and on return takes up paid employment. That is a success of sorts.

Poor Richard – study resources

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle edition – Amazon US

![]() Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon UK

Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon US

Complete Stories 1864—1874 – Library of America – Amazon US

![]() The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to Henry James – Amazon UK

![]() Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Henry James at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Henry James at Mantex – tutorials, biography, study resources

Poor Richard – plot summary

Part I. Wastrel and poor orphan Richard Maule is in love with rich Gertrude Whittaker. He tries to persuade her to love him, and even proposes marriage. But she offers him only friendship in return, plus a willingness to help him ‘improve’.

Part II. Richard and Gertrude are old school friends. She has inherited a lot of money from her father. Richard has done virtually nothing except work on the farm he has inherited and allowed to run down. But the prospect of winning Gertrude inspires him to reform his life. Gertrude meanwhile decides it will help Richard if she introduces him to Captain Severn.

Part III. Severn is a serious, honourable, but poor man who accepts Gertrude’s comforts when he is injured in the Civil War. But he hasn’t enough money to marry, so they remain just good friends.

Gertrude invites Richard and Severn to meet each other – but they are joined unexpectedly by Major Lutterel and the event is ruined. Richard feels ill at ease in this more sophisticated company.

Part IV. After tea, they all go for a walk, during which Richard and Severn exchange opinions on Gertrude, and realise that they are rivals for her favour. Richard gauchely tries to impress everyone with his knowledge of the local river. There is a complex tension of competition between all three men for Gertrude’s attention.

Part V. Richard cultivates a regime of hard work and self-denial, hoping to overcome his obsession with Gertrude. One day he rides over to see her, only to discover Captain Severn just leaving and Gertrude very upset. Richard accuses her of being in love with Severn.

She is in fact holding out against both Severn and Richard, and it brings her little joy. But on mature reflection, she begins to see positives in Richard’s simplicity She drives over to his farm where he is apologetic for his behaviour. His courtesy and simple behaviour win her over.

News arrives of a defeat for the Unionists in the Civil War in Virginia. Richard and Major Lutterel leave Gertrude’s house, only to meet Captain Severn on his way to pay her his last respects before re-joining his regiment. Richard lies to Severn about Gertrude being away from home, and Major Lutterel is complicit in the deception, because he wishes to keep away all rivals, having decided that he wishes to marry Gertrude himself.

Richard wishes to reveal his guilt to Gertrude about the deception, but fails to do so because she receives him in a very neutral manner. He goes home with Major Lutterel, gets drunk, and by next day he is very ill with typhoid fever.

Part VI. Colonel Lutterel arrives at Gertrude’s house with the news of Richard’s illness. They drive over to see him, and Gertrude arranges nursing support for him. Whilst Richard is ill, Colonel Lutterel increases the intensity of his attentions to Gertrude, who although she is not in love with him is prepared to countenance a possible alliance.

The Major arrives at Gertrude’s house with the news that Richard is getting better and Captain Severn has been killed. He asks her to marry him, and although she tells him she does not love him, she is prepared to accept the offer.

Part VII. Gertrude makes her preparations for the marriage in secret, with a heavy heart. Major Lutterel visits Richard, where he denies having any news of Captain Severn, and reveals that he is engaged to Gertrude. Richard takes a stoical view, and hopes that his disappointment will help him recover. When he meets Gertrude she is pale and unhappy: he implores her to give up the plan to marry Major Lutterel. Suddenly Major Lutterel arrives, and Richard reveals the truth about Captain Severn’s last failed visit to see Gertrude. Gertrude breaks off her engagement with Lutterel and forgives Richard.

Richard sells the farm, pays off his debts, and joins the war. When he returns at the end of the war he finds employment in his old neighbourhood. Gertrude also sells up, and goes to live in Florence.

Poor Richard – principal characters

| Richard Maule | a poor orphan of twenty-four |

| Gertrude Whittaker | a rich young woman of twenty-four |

| Fanny Maule | Richard’s sister, a friend of Gertrude |

| Captain Edmund Severn | a Unionist soldier of twenty-eight |

| Major Lutterel | a recruiting officer of thirty-six with no money |

| Mrs Martin | Captain Severn’s sister |

Further reading

Biographical

![]() Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Theodora Bosanquet, Henry James at Work, University of Michigan Press, 2007.

![]() F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

F.W. Dupee, Henry James: Autobiography, Princeton University Press, 1983.

![]() Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

Leon Edel, Henry James: A Life, HarperCollins, 1985.

![]() Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

Philip Horne (ed), Henry James: A Life in Letters, Viking/Allen Lane, 1999.

![]() Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Henry James, The Letters of Henry James, Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

![]() Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Fred Kaplan, Henry James: The Imagination of Genius, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

![]() F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

F.O. Matthieson (ed), The Notebooks of Henry James, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Critical commentary

![]() Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

Elizabeth Allen, A Woman’s Place in the Novels of Henry James London: Macmillan Press, 1983.

![]() Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Ian F.A. Bell, Henry James and the Past, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

![]() Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

Millicent Bell, Meaning in Henry James, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1993.

![]() Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Harold Bloom (ed), Modern Critical Views: Henry James, Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

![]() Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

Kirstin Boudreau, Henry James’s Narrative Technique, Macmillan, 2010.

![]() J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

J. Donald Crowley and Richard A. Hocks (eds), The Wings of the Dove, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1978.

![]() Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Victoria Coulson, Henry James, Women and Realism, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

Daniel Mark Fogel, A Companion to Henry James Studies, Greenwood Press, 1993.

![]() Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

Virginia C. Fowler, Henry James’s American Girl: The Embroidery on the Canvas, Madison (Wis): University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

![]() Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Jonathan Freedman, The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

Judith Fryer, The Faces of Eve: Women in the Nineteenth Century American Novel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976

![]() Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

Roger Gard (ed), Henry James: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge, 1968.

![]() Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Tessa Hadley, Henry James and the Imagination of Pleasure, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

![]() Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

Barbara Hardy, Henry James: The Later Writing (Writers & Their Work), Northcote House Publishers, 1996.

![]() Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Richard A. Hocks, Henry James: A study of the short fiction, New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

![]() Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Donatella Izzo, Portraying the Lady: Technologies of Gender in the Short Stories of Henry James, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

![]() Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

Colin Meissner, Henry James and the Language of Experience, Cambridge University Press, 2009

![]() John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

John Pearson (ed), The Prefaces of Henry James, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

![]() Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Richard Poirer, The Comic Sense of Henry James, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

![]() Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Hugh Stevens, Henry James and Sexuality, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

![]() Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Merle A. Williams, Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

![]() Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Judith Woolf, Henry James: The Major Novels, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

![]() Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Ruth Yeazell (ed), Henry James: A Collection of Critical Essays, Longmans, 1994.

Other works by Henry James

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

Washington Square (1880) is a superb early short novel, It’s the tale of a young girl whose future happiness is being controlled by her strict authoritarian (but rather witty) father. She is rather reserved, but has a handsome young suitor. However, her father disapproves of him, seeing him as an opportunist and a fortune hunter. There is a battle of wills – all conducted within the confines of their elegant New York town house. Who wins out in the end? You will probably be surprised by the outcome. This is a masterpiece of social commentary, offering a sensitive picture of a young woman’s life.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

The Aspern Papers (1888) is a psychological drama set in Venice which centres on the tussle for control of a great writer’s correspondence. An elderly lady, ex-lover of the writer, seeks a husband for her daughter. But the potential purchaser of the papers is a dedicated bachelor. Money is also at stake – but of course not discussed overtly. There is a refined battle of wills between them. Who will win in the end? As usual, James keeps the reader guessing. The novella is a masterpiece of subtle narration, with an ironic twist in its outcome. This collection of stories also includes three of his accomplished long short stories – The Private Life, The Middle Years, and The Death of the Lion.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

The Spoils of Poynton (1896) is a short novel which centres on the contents of a country house, and the question of who is the most desirable person to inherit it via marriage. The owner Mrs Gereth is being forced to leave her home to make way for her son and his greedy and uncultured fiancee. Mrs Gereth develops a subtle plan to take as many of the house’s priceless furnishings with her as possible. But things do not go quite according to plan. There are some very witty social ironies, and a contest of wills which matches nouveau-riche greed against high principles. There’s also a spectacular finale in which nobody wins out.

![]() Buy the book from Amazon UK

Buy the book from Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book from Amazon US

Buy the book from Amazon US

Henry James – web links

Henry James at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides, tutorials on the Complete Tales, book reviews. bibliographies, and web links.

The Complete Works

Sixty books in one 13.5 MB Kindle eBook download for £1.92 at Amazon.co.uk. The complete novels, stories, travel writing, and prefaces. Also includes his autobiographies, plays, and literary criticism – with illustrations.

The Ladder – a Henry James website

A collection of eTexts of the tales, novels, plays, and prefaces – with links to available free eTexts at Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

A Hyper-Concordance to the Works

Japanese-based online research tool that locates the use of any word or phrase in context. Find that illusive quotable phrase.

The Henry James Resource Center

A web site with biography, bibliographies, adaptations, archival resources, suggested reading, and recent scholarship.

Online Books Page

A collection of online texts, including novels, stories, travel writing, literary criticism, and letters.

Henry James at Project Gutenberg

A major collection of eTexts, available in a variety of eBook formats.

The Complete Letters

Archive of the complete correspondence (1855-1878) work in progress – published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Scholar’s Guide to Web Sites

An old-fashioned but major jumpstation – a website of websites and resouces.

Henry James – The Complete Tales

Tutorials on the complete collection of over one hundred tales, novellas, and short stories.

© Roy Johnson 2013

More tales by James

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Sense and Sensibility (1811) casts two young and marriageable sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood as representatives of ‘sense’ and ‘sensibility’ respectively. Elinor bears her social disappointments with dignity and restraint – and thereby gets her man. Marianne on the other hand is excitable and impetuous, following her lover to London – where she quickly becomes disillusioned with him. Recovering and gaining more ‘sense’, she then finally sees the good qualities in her old friend Colonel Brandon, who has been waiting in the wings and is now conveniently on hand to propose marriage.

Sense and Sensibility (1811) casts two young and marriageable sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood as representatives of ‘sense’ and ‘sensibility’ respectively. Elinor bears her social disappointments with dignity and restraint – and thereby gets her man. Marianne on the other hand is excitable and impetuous, following her lover to London – where she quickly becomes disillusioned with him. Recovering and gaining more ‘sense’, she then finally sees the good qualities in her old friend Colonel Brandon, who has been waiting in the wings and is now conveniently on hand to propose marriage. Northanger Abbey (1818) opens in the drawing rooms of Bath. The heroine is imaginative Catherine Morland who falls in love with Henry Tilney, a young clergyman. When he invites her to meet his family at the Abbey however, she sees nothing but Gothic melodrama at every turn – since they were very fashionable at the time. Her visions of medieval horror prove groundless of course. This is Jane Austen’s satirical critique of Romantic cliché and excess. But Catherine eventually learns to see the world in a realistic light – and gets her man in the end. This volume also contains the early short novels Lady Susan and The Watsons, as well as the unfinished Sanditon.

Northanger Abbey (1818) opens in the drawing rooms of Bath. The heroine is imaginative Catherine Morland who falls in love with Henry Tilney, a young clergyman. When he invites her to meet his family at the Abbey however, she sees nothing but Gothic melodrama at every turn – since they were very fashionable at the time. Her visions of medieval horror prove groundless of course. This is Jane Austen’s satirical critique of Romantic cliché and excess. But Catherine eventually learns to see the world in a realistic light – and gets her man in the end. This volume also contains the early short novels Lady Susan and The Watsons, as well as the unfinished Sanditon. Mansfield Park (1814) is more serious after the comedy of the earlier novels. Heroine Fanny Price is adopted into the family of her rich relatives. She is long-suffering and passive to a point which makes her almost unappealing – but her refusal to tolerate any drop in moral standards eventually teaches lessons to all concerned. (All that is except standout character Mrs Norris who is a sponging and interfering Aunt you will never forget.) The hero Edmund is dazzled by sexually attractive Mary Crawford – but in the nick of time sees the error of his ways and marries Fanny instead. Slow moving, but full of moral subtleties.

Mansfield Park (1814) is more serious after the comedy of the earlier novels. Heroine Fanny Price is adopted into the family of her rich relatives. She is long-suffering and passive to a point which makes her almost unappealing – but her refusal to tolerate any drop in moral standards eventually teaches lessons to all concerned. (All that is except standout character Mrs Norris who is a sponging and interfering Aunt you will never forget.) The hero Edmund is dazzled by sexually attractive Mary Crawford – but in the nick of time sees the error of his ways and marries Fanny instead. Slow moving, but full of moral subtleties. Emma (1816) Charming and wilful Emma Woodhouse amuses herself by dabbling in other people’s affairs, planning their lives the way she sees fit. Most of her match-making plots go badly awry, and moral confusion reigns until she abandons her self-delusion and wakes up to the fact that stern but honourable Mr Knightly is the right man for her after all. As usual, money and social class underpin everything. Some wonderful comic scenes, and a rakish character Frank Churchill who finally reveals his flaws by making the journey to London just to get his hair cut.

Emma (1816) Charming and wilful Emma Woodhouse amuses herself by dabbling in other people’s affairs, planning their lives the way she sees fit. Most of her match-making plots go badly awry, and moral confusion reigns until she abandons her self-delusion and wakes up to the fact that stern but honourable Mr Knightly is the right man for her after all. As usual, money and social class underpin everything. Some wonderful comic scenes, and a rakish character Frank Churchill who finally reveals his flaws by making the journey to London just to get his hair cut. Persuasion (1818) is the most mature of her novels, if one of the least exciting. Heroine Anne Elliott has been engaged to Captain Wentworth, but has broken off the engagement in deference to family and friends. Meeting him again eight years later, she goes against conventional wisdom and accepts his second proposal of marriage. Anne is a sensitive and thoughtful character, quite unlike some of the earlier heroines. Jane Austen wrote of her “She is almost too good for me”. There is a shift of location to Lyme Regis for this novel, which reveals for the first time a heroine acting from a deep sense of personal conviction, against the grain of conventional wisdom.

Persuasion (1818) is the most mature of her novels, if one of the least exciting. Heroine Anne Elliott has been engaged to Captain Wentworth, but has broken off the engagement in deference to family and friends. Meeting him again eight years later, she goes against conventional wisdom and accepts his second proposal of marriage. Anne is a sensitive and thoughtful character, quite unlike some of the earlier heroines. Jane Austen wrote of her “She is almost too good for me”. There is a shift of location to Lyme Regis for this novel, which reveals for the first time a heroine acting from a deep sense of personal conviction, against the grain of conventional wisdom.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Lord Jim

Lord Jim Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man from the South to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page. What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book.

What Masie Knew (1897) A young girl is caught between parents who are in the middle of personal conflict, adultery, and divorce. Can she survive without becoming corrupted? It’s touch and go – and not made easier for the reader by the attentions of an older man who decides to ‘look after’ her. This comes from the beginning of James’s ‘Late Phase’, so be prepared for longer and longer sentences. In fact it’s said that whilst composing this novel, James switched from writing longhand to using dictation – and it shows if you look carefully enough – part way through the book. The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.

The Ambassadors (1903) Lambert Strether is sent from America to Paris to recall Chadwick Newsome, a young man who is reported to be compromising himself by an entanglement with a wicked woman. However, Strether’s mission fails when he is seduced by the social pleasures of the European capital, and he takes Newsome’s side. So a second ambassador is dispatched in the form of the more determined Sarah Pocock. She delivers an ultimatum which is resisted by the two young men, but then an accident reveals unpleasant truths to Strether, who is faced by a test of loyalty between old Europe and the new USA. This edition presents the latest scholarship on James and includes an introduction, notes, selected criticism, a text summary and a chronology of James’s life and times.