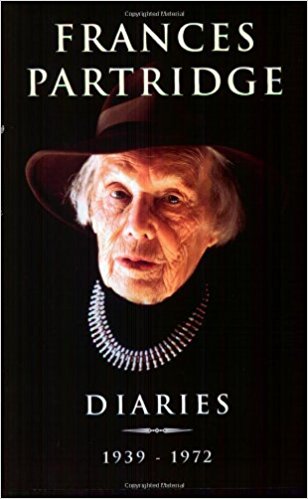

Bloomsbury socialite, diarist, and translator

Frances Partridge (1900-2004) was a fringe member of the Bloomsbury Group, but someone who outlived all the other major figures. She knew Lytton Strachey and Dora Carrington, and she married Ralph Partridge after his first wife’s suicide. She also became a prolific diarist and a translator of novels from the original Spanish.

She was born Francis Marshall into a prosperous upper middle class family that already had its roots in Bloomsbury. Her father was a friend of Sir Leslie Stephen, and the family lived in a grand home at 28 Bedford Square, with the Asquiths and the literary critic Walter Raleigh as neighbours. There was also a second home in Hindhead, Surrey to which the family transferred in 1908.

At school she befriended Julia Strachey, through whose family she became acquainted with the Stephens – Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf and their bothers. Both Julia and Frances transferred to the prestigious (and very expensive) Beadales public school by the start of the war in 1914.

Frances developed an interest in philosophy and actually met the author of her favourite textbook, Bertrand Russell. In the non-conformist ethos of the school, she became a pacifist, which given the jingoist fervour during the years of the First World War, was quite a radical attitude.

In 1918 she went to the all-female Newnham College Cambridge, where women students studied the same courses as men but could not be awarded degrees. [Cambridge was the last university in England to give women equal status in 1948.]

She studied English under I.A. Richards. Later she switched from English to philosophy, and eventually met Ludwig Wittgenstein who was teaching there at the time. She finished undergraduate studies with a 2:I and the same year her father died, leaving her a large inheritance, though she did not go to his funeral.

Her first job was as assistant in the bookshop run by David Garnett, who had become her brother-in-law by marrying her sister Ray (Rachel). The business was badly run, but was patronised by senior members of the Bloomsbury Group and its various connections, with all of whom Frances became friendly.

The closest of these connections were with Dora Carrington and her husband Ralph Partridge, who lived in a curious menage a trois with Lytton Strachey in a country mill house in Tidmarsh (Berkshire). This was a trio which Carrington was in the dangerous process of turning into an even more complex quartet by having an affair with Ralph Partridge’s best friend Gerald Brenan at the same time.

Given the flagrant bed-hopping of the people with whom she was mixing, Frances’ behaviour seems more like that of a professional virgin. She kept three men dangling at once and even in her mid-twenties thought it would ruin her reputation if she was known to be alone in Paris at the same time as Ralph Partridge.

Eventually she went on a holiday alone with Partridge to Spain, relinquished her virginity, and on return expected him to show his commitment by setting up home with her. Instead, he behaved like the traditional cad who wants the pleasure of a mistress but pleads he cannot possibly leave his wife.

She kept her two other male admirers waiting whilst he negotiated with his housemates Lytton and Dora. After a lot of agonising they all finally reached a compromise. Frances and Ralph moved into James and Alix Strachey’s empty flat in Gordon Square, from which Ralph was free to visit his wife at weekends.

This move put Frances right into the heart of Bloomsbury – geographically, socially, and intellectually. But a sour note was introduced into the mix when after a while Lytton announced that they wanted to see less of her.

Social and emotional tensions continued to smoulder between the four individuals, but matters were eventually resolved by a tragic if very symmetrical sequence of events. First there was sudden death of Lytton Strachey from stomach cancer. Following this was Carrington’s reaction to it when she committed suicide. Ralph was suddenly left a widower with a substantial inheritance from his dead wife and ownership of the country house they had bought at Ham Spray (near Reading).

The following year Frances and Ralph had a low key marriage, and she had a miscarriage. These events were followed by the first of Ralph’s many extra-marital affairs, which Frances dealt with as if she were suffering from a headache or a heavy cold.

Her wifely patience was subsequently rewarded with the birth of her son Burgo who was immediately put into a nursery in an annex to the house and raised by hired help. The parents went off for an extended holiday with Gerald Brenan to Malaga.

In the period that followed, the Spanish Civil War and Hitler’s incursions in middle-Europe put a strain on the political beliefs and the internationalism of the Bloomsbury Group – but Frances remained adamantly pacifist. For her, nothing could be worse than war.

During the war itself she seemed to suffer nothing worse than a lack of domestic help. Staff left to join the war effort, and she couldn’t cook. Fortunately, there were still oysters and plovers at the Ivy restaurant on excursions into town.

In the after-war years there were problems with her son Burgo who had persistent fears that his parents were dead (which was psychologically understandable). There was a failed project to write an encyclopedia of English botany. Both Frances and Ralph lived on inherited wealth, and neither of them had proper jobs – but Ralph eventually wrote a history of Broadmoor Prison, whilst Frances took up the task of indexing the English edition of Freud’s complete works, which was published by the Hogarth Press.

In 1950 Ralph Partridge died of a heart attack. Frances subsequently, but with great emotional difficulty, sold the house at Ham Spray and moved to a small flat in Belgravia. Her young son Burgo married the even younger daughter of David Garnett. This created a third generational link in the complex matrix of Bloomsbury inter-connections, but less than a year later the young man was dead, killed by an aortic aneurysm.

Frances dealt with these personal losses by a combination of writing and travel. She worked as a translator (including the novels of Alejo Carpentier) and visited Gerald Brenan in Spain on a fairly regular basis. She also spent a lot of time looking after Julia Strachey, who was falling victim to dementia.

In the years that followed, as one of its oldest surviving members, she became an unofficial but certainly unelected guardian of Bloomsbury reputations – most noticeably that of her former husband Ralph. She wanted to protect all her old friends from misrepresentation and vulgarisation. She had battles with the BBC and Ken Russell, but even more with Gerald Brenan, who was in the process of writing his autobiography.

In her eighties she entered on an amazingly productive phase – three books of memoirs in as many years, including the best-selling Love in Bloomsbury, In fact the success of this venture led to a spate of publications over the next decade.

She lived to be over a hundred years old, outliving her exact contemporary the Queen Mother, but as she characteristically insisted, ‘living alone, rather than being waited on hand and foot’.

© Roy Johnson 2018

Francis Partridge – Buy the book at Amazon UK

Frances Partridge – Buy the book at Amazon US

Anne Chisholm, Frances Partridge: The Biography, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2009, pp.402, ISBN: 0297646737

More on biography

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on literary studies

More on the arts

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis Amerika

Amerika

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987) was born in Malta, the son of an English army officer. After spending some of his childhood in South Africa and India, he grew up in an isolated Cotswold village. He studied at Radley College and then the military academy at Sandhurst. Travel and adventure were to be his way of life, and at sixteen he ran away from home. His aim was to reach Central Asia but the outbreak of the Balkan War and shortage of money caused him to return to England. He studied to enter the Indian Police (as did his near-contemporary

Gerald Brenan (1894-1987) was born in Malta, the son of an English army officer. After spending some of his childhood in South Africa and India, he grew up in an isolated Cotswold village. He studied at Radley College and then the military academy at Sandhurst. Travel and adventure were to be his way of life, and at sixteen he ran away from home. His aim was to reach Central Asia but the outbreak of the Balkan War and shortage of money caused him to return to England. He studied to enter the Indian Police (as did his near-contemporary  South from Granada

South from Granada The Spanish Labyrinth

The Spanish Labyrinth

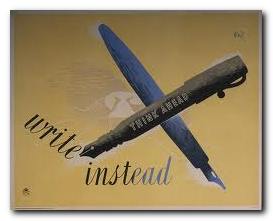

But the GPO has from its earliest years made a habit of commissioning artists to design posters to promote its services and reminding us to post early for Xmas. In fact there has been a quite deliberate campaign to both educate the public and promote an impression of efficient, modern technology driving communications at a national level. This has been coupled ideologically with folksy images of the village postman delivering letters in all weathers, and at the same time promoting an empire of connectivity that embraced the globe.

But the GPO has from its earliest years made a habit of commissioning artists to design posters to promote its services and reminding us to post early for Xmas. In fact there has been a quite deliberate campaign to both educate the public and promote an impression of efficient, modern technology driving communications at a national level. This has been coupled ideologically with folksy images of the village postman delivering letters in all weathers, and at the same time promoting an empire of connectivity that embraced the globe. The range of artists and designers they did use included

The range of artists and designers they did use included