critical biography of major but under-appreciated singer

I have to confess that I only heard of Jimmy Scott quite recently. Understandably so, it turns out. He’s one of the best kept secrets in the world of jazz and ballad singing. I heard his voice on a radio broadcast, was intrigued, bought a couple of CDs from Amazon – and was completely blown away. He’s completely unlike any other male singer you’ve ever heard of – mainly because he sounds like a woman. This is the result of a congenital disease which denied him puberty.

But that isn’t all: he has a style which is stripped bare to a minimum and yet very mannered at the same time. Like all good jazz musicians, he pays attention to song lyrics and sings them as if he means them. The most interesting things about him are his voice quality – high falsetto, big vibrato – and his delivery, which is laid back to a point where you think he might fall over. But he never does. The nearest style I can think of is Billie Holliday – one of his early fans and an influence. As David Ritz puts it in this very readable biography:

But that isn’t all: he has a style which is stripped bare to a minimum and yet very mannered at the same time. Like all good jazz musicians, he pays attention to song lyrics and sings them as if he means them. The most interesting things about him are his voice quality – high falsetto, big vibrato – and his delivery, which is laid back to a point where you think he might fall over. But he never does. The nearest style I can think of is Billie Holliday – one of his early fans and an influence. As David Ritz puts it in this very readable biography:

The rhythms he creates are wholly original. He does more than take his time. He doesn’t worry about time. Time disappears as a restraint or a measure. As a singer, his signatures are idiosyncratic phrasing and radical, behind-the beat syncopation. His career, like his singing, has lagged far behind the beat.

Scott’s life was full of personal heartbreak: from a dysfunctional family; orphaned as a teenager; married four times; duped by record producers; constantly on the move; scorned as an outsider; drink, (soft) drugs. He lived, as David Ritz accurately puts it, the jazz life.

Oddly enough, he claims that his early influences were Paul Robeson and Judy Garland two singers who you would think were at opposite ends of the musical spectrum.

The amazing thing, for someone who is still alive and singing now (I heard him with a German tenor player only a few weeks ago) is that he cut his musical teeth with people such as Lester Young, Charlie Parker, and Tadd Dameron. His working life spans the last half-century.

Much of the racy vivacity of Ritz’s narrative comes from the fact that he transcribes the accounts of people he interviewed in his research. There are also some very entertaining vignettes along the way – such as life on the road in the high-octane Lionel Hampton band in the late 1940s.

His biggest fans were the people who matter musically – Bird, B.B.King, Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, Billie Holiday, and Shirley Horn. Later on he was championed by Lou Reed and Madonna.

And his own musical taste is impeccable – as in his perceptive observation that Stan Getz got better as he got older “Whatever he learned from Lester—and he learned a lot—he expanded on the lessons until he became a master himself”

He started out promisingly enough, but every time he tried to make his breakthrough record albumn, an old producer would surface to block his ambition with a ‘cease and desist’ order straight out of a nineteenth century melodrama. Scott remained unembittered – though it has to be said he took out a lot of his anger on the people closest to him.

The 1970s and 1980s are like waste years, with Scott working as a hotel lift attendant and a shipping clerk to make ends meet. Then there are a succession of failed enterprises which left him living off social security. But then he finally got some recognition and success in the 1990s when largely white audiences began to catch on to him. By then he was sixty-eight years old.

So the story has a reasonably happy ending – but he had to wait almost half a lifetime for it. This is an enthralling account of a real survivor, recounted with genuine but not uncritical admiration, and supported by a scholarly apparatus of bibliography and discography which left me yearning to read and listen to more of this truly remarkable artist.

© Roy Johnson 2002

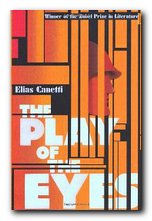

David Ritz, Faith in Time: The Life of Jimmy Scott, Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002, pp.270, ISBN: 0306812290

More on music

More on media

More on lifestyle