a tutorial essay with study resources

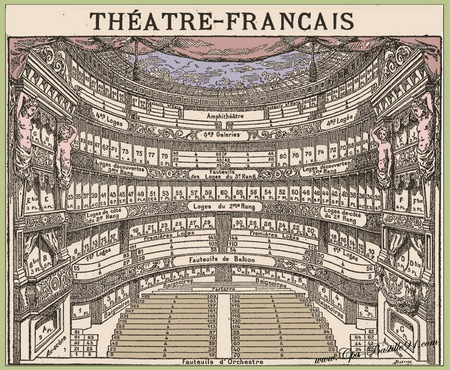

Novelists and the theatre have often formed an ambiguous relationship. Some of the earliest novelists such as Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett produced both novels and dramas (as well as non-fiction works) though they are currently regarded primarily as novelists and their writing for the theatre is more or less forgotten.

The same is true for Walter Scott, and even Jane Austen has a play (Sir Charles Grandison) amongst her lesser, that is almost completely unknown works. Charles Dickens was also a great lover of amateur theatricals, participating in them as an actor and a stage manager. He wrote a play The Frozen Deep (1856) in conjunction with his friend Wilkie Collins, based on Sir John Franklin’s search for the Northwest Passage. But despite rave reviews this work is now a museum piece, whilst his novels are as popular as ever.

It is difficult to pinpoint a cause for this phenomenon of failed theatrical works, except to say that as the novel rose as a medium of both popular and highbrow cultural values, the theatre was in a period of relative decline. From the eighteenth into the nineteenth centuries more and more people were literate. Newspapers and magazines (in which many novels first appeared) grew in popularity, whereas the number of theatres remained relatively static. Circulating libraries grew in popularity, as did the sales of novels in both serial and volume form.

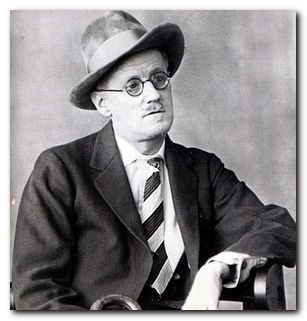

In the twentieth century works of a theatrical nature came to be transmitted first via cinema, then radio, and finally by television, which is now established as the most popular medium for the expression of imaginative drama. The crossover from the dominance of one medium over another is nowhere more neatly illustrated than in the case of James Joyce – one of the most experimental of modern novelists – who was the first person to open a cinema in Dublin, Ireland in 1909.

Here are a few examples of novelists and their attempts to diversify in terms of their medium. Perhaps their lack of theatrical success can also be attributed to the enormous shift in artistic practice that the switch from page to stage inherently demands.

Henry James is a very famous case of the ambivalent results of a novelist’s dalliance with the theatre. His novels are packed with dramatic incident, sparkling dialogue, and well-orchestrated plots – so he had every reason to believe that he would succeed in writing staged dramas. From 1890 onwards he wrote half a dozen plays, but only one of them – a dramatization of his novel The American (1876) – was produced with any degree of success.

Then in 1895 he put all his energy into the long drama Guy Domville which he wrote especially for the opening of the St James’s Theatre in the West End of London. This proved to be a disaster, and James the playwright was booed off stage on the first night. He was seriously depressed by this response, and was forced to return to the novel genre as the principal outlet for his creative imagination.

However, the story does have a positive ending, because he recycled the content of these dramas into the plots of some of his later novels such as The Other House (1896) and The Outcry (1911). Interestingly enough, James converted The Other House back into play form in 1909, but once again it failed to reach production.

![]() Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of Henry James – Kindle – Amazon US

Thomas Hardy gave up writing novels because of the public outcries of indecency over Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) and Jude the Obscure (1894). Afterwards he turned his attention to the ‘theatre’ and spent six years writing his epic verse drama The Dynasts. This huge panorama of the Napoleonic War was published in three parts, nineteen acts, and one hundred and thirty scenes in 1904, 1906, and 1908. It is written in verse, and is more or less impossible to present on stage because of its complex battle scenes and its sheer length.

It is worth noting that many other nineteenth century poets and writers had written verse dramas which are now confined to the of literary history – from Shelley’s The Cenci (1819), to Browning’s series more than half a dozen verse dramas published under the collective title of Bells and Pomegranates which were published but hardly ever produced on stage

Hardy’s The Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall is a one act play published in 1923 and first performed by the Hardy Players, an amateur theatrical group for whom Hardy wrote the drama. The full title reflects his desire to have the play performed: The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall at Tintagel in Lyonnesse. A New Version of an Old Story Arranged as a Play for Mummers, in One Act Requiring No Theatre or Scenery.

![]() Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of Thomas Hardy – Kindle – Amazon US

Joseph Conrad had established his reputation as the author of technically challenging and morally complex novels when he first felt drawn to the world of theatre. He might have known that the result would be problematic, because he immediately ran into the issue of censorship. At that time all works written for the stage had to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s office for approval by the Censor of Plays. This is a power which was not repealed until the Theatres Act of 1968.

In 1905 he wrote One Day More a one-act play which was an adaptation of his story To-Morrow (1902). The play was actually a modest success, but Conrad felt the experiment was a disappointment. However, he was outraged by the arbitrary legal requirement and he railed against the public censorship of dramatic productions by the Lord Chamberlain in his very scathing essay The Censor of Plays – An Appreciation (1907), speaking of

th[is] monstrous and outlandish figure, the magot chinois whom I believed to be but a memorial of our forefathers’ mental aberration, that grotesque potiche

However, despite this unsatisfactory experience, he embarked on further theatrical ventures, none of which were particularly successful. In 1920 he was persuaded to adapt his story Gaspar Ruiz for the cinema and produced a film script with the title Gaspar the Strong Man, but the cinematic version was never produced.

He adapted his novel The Secret Agent (1904) for the theatre – a play staged with reasonable success at the Ambassadors Theatre in 1922, but which he felt to be a failure:

The disagreeable part of this business is to see wasted the hard work of people who depend upon it for their livelihood [the actors], and for whom success would mean assured employment and ease of mind. One feels guilty somehow.

Then in 1922 he wrote a play Laughing Anne which was criticised by his friend John Galsworthy as being technically naive and ‘threatening to present an unbearable spectacle’. This was because the original story, Because of the Dollars (1914) features a man with no hands who bludgeons a woman to death. It proved to be his last attempt at writing for the theatre.

A comparison of the play script and the story reveals the weaknesses of the theatrical version. The play reaches its dramatic climax with a fight sequence in which Laughing Anne is killed by the man without hands (MWH). All the action takes place in semi-darkness.

DAVIDSON (To SERANG on board) : Send four men ashore. There is a dead body there which we are going to take out to sea, (He moves, carrying the lantern low, followed by four Malays in blue dungaree suits, dark faces. Stands the lantern on the ground by the body and looking down at it apostrophizes the corpse.) Poor Anne! You are on my conscience, but your boy shall have his chance.

(As the kalashes stoop to lift up the body CURTAIN falls.)

Quite apart from all the superfluous scene description, this version omits some of the key events and the ironic aftermath to the story. In the prose narrative Because of the Dollars Davidson buries Anne at sea and gives the child to his wife to look after. However, his wife suspects that the child is actually his by Anne, and she turns against both of them. Eventually she leaves him and goes back to her parents. The boy is sent to a church school in Malacca, where he eventually does well and plans to become a missionary. Davidson is left alone with nobody.

In 1924, as a fellow novelist and author of plays, Galsworthy accurately summed up Conrad’s relationship to the theatre:

his nature recoiled too definitely from the limitations which the stage imposes on word painting and the subtler efforts of a psychologist. The novel suited his nature better than the play, and he instinctively kept to it.

![]() Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of Joseph Conrad – Kindle – Amazon US

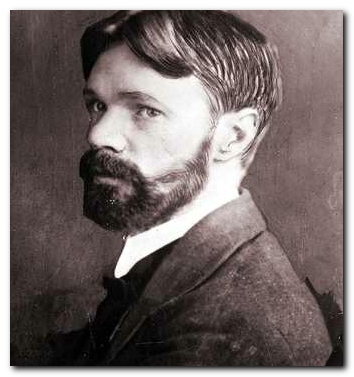

D.H. Lawrence is well known as a novelist, a writer of short stories, and even as a poet; but the amazing thing is that he wrote eight plays, only a couple of which were staged during his own lifetime. The full list is as follows: The Daughter-in-Law (1912); The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd (1914); Touch and Go (1920); David (1926); The Fight for Barbara (1933); A Collier’s Friday Night (1934); The Married Man (1940); The Merry-Go-Round (1941).

Many of these works anticipate the ‘kitchen sink’ phase of British drama which emerged later in the 1950s and 1960s. They dealt in a fully realistic manner with powerful conflicts of class, gender, and individual liberty set in working class milieux. A number of these works have been successfully staged and turned into television dramas in the twentieth century – but they have had little impact on his critical reputation, which remains firmly based on his work as a novelist and writer of short stories.

![]() Complete Works of D.H. Lawrence – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of D.H. Lawrence – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of D.H. Lawrence – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of D.H. Lawrence – Kindle – Amazon US

James Joyce had only published a short selection of poems (Chamber Music 1907) a collection of short stories (Dubliners 1914) and his first novel (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man 1916) when he produced his only play Exiles in 1918. He had been heavily influenced by the work of the Norwegian dramatist Ibsen whose powerful dramas had challenged many of the suppositions that lay behind public and private morality in the late nineteenth century.

Exiles was rejected by W.B. Yeats for production at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, and it had to wait until 1970 for a major London performance when it was directed by Harold Pinter at the Mermaid Theatre.

![]() Complete Works of James Joyce – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of James Joyce – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of James Joyce – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of James Joyce – Kindle – Amazon US

Virginia Woolf had no serious intention to be considered a playwright, but she did take part in amateur theatrical productions mounted by members of the Bloomsbury Group for their own amusement, and she did eventually write the play Freshwater. This is a satire of the bohemian world of her aunt, the Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. But Woolf took the play seriously enough to produce two versions – a one act version in 1923, and then a longer three act version in 1935.

![]() Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2016

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

Following Sasha’s return to Russia, the desolate, lonely Orlando returns to writing The Oak Tree, a poem started and abandoned in his youth. This period of contemplating love and life leads him to appreciate the value of his ancestral stately home, which he proceeds to furnish lavishly and then plays host to the populace. Ennui sets in and a persistent suitor’s harassment leads to Orlando’s appointment by King Charles II as British ambassador to Constantinople. Orlando performs his duties well, until a night of civil unrest and murderous riots. He falls asleep for a lengthy period, resisting all efforts to rouse him.

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse The Complete Shorter Fiction

The Complete Shorter Fiction The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

The Bloomsbury Group is a short but charming book, published by the National Portrait Gallery. It explores the impact of Bloomsbury personalities on each other, plus how they shaped the development of British modernism in the early part of the twentieth century. But most of all it’s a delightful collection of portrait paintings and photographs, with biographical notes. It has an introductory essay which outlines the development of Bloomsbury, followed by a series of portraits and the biographical sketches of the major figures.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, close reading, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic.