literary criticism and commentary

T.E. Apter, Virginia Woolf: A Study of her Novels, New York: New York University Press, 1979.

Anne Oliver Bell and Andrew McNeillie, The Diary of Virginia Woolf, London: Hogarth Press, 5 volumes, 1977-1984.

Quentin Bell, Bloomsbury, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968.

Quentin Bell, Virginia Woolf: a Biography, 2 Vols, London: Hogarth Press, 1972.

Joan Bennett, Virginia Woolf: Her Art as a Novelist, second edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964.

Rachel Bowley, Virginia Woolf: Feminist Dimensions, Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

Maria Di Battista, Virginia Woolf’s Major Novels, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1980.

David Daiches, Virginia Woolf, second edition, Norfolk Conn.: New Directions, 1963

Susan Dick (ed), The Complete Shorter Fiction of Virginia Woolf, Hogarth Press, 1985.

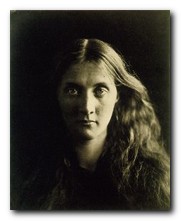

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject. Ideal for beginners.

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject. Ideal for beginners. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Avron Fleishman, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Reading, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

Ralph Freedman, Virginia Woolf: Revaluation and Continuity, Berkley: University of California Press, 1980.

B.J. Kirkpatrick, A Bibliography of Virginia Woolf, second edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Lyndall Gordon, Virginia Woolf: A Writer’s Life, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Jean Guiguet, Virginia Woolf and her Works, trans. Jean Stewart, London: Hogarth Press, 1965.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Virginia Woolf’s ‘Mrs Dalloway’: a Study in Alienation, Sussex University Press, 1975.

Mitchell A. Leaska, The Novels of Virginia Woolf: From Beginning to End, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1977.

Hermione Lee, The Novels of Virginia Woolf, London: Methuen, 1977.

Robin Majumdar and Allen McLaurin (eds), Virginia Woolf: The Critical Heritage, London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1975.

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf is collection of essays which addresses the full range of her intellectual perspectives – literary, artistic, philosophical and political. It provides new readings of all nine novels and fresh insight into Woolf’s letters, diaries and essays. The progress of Woolf’s thinking is revealed from Bloomsbury aestheticism through her hatred of censorship, corruption and hierarchy to her concern with all aspects of modernism. This book explores the immense range of social and political issues behind her search for new forms of narrative.

The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf is collection of essays which addresses the full range of her intellectual perspectives – literary, artistic, philosophical and political. It provides new readings of all nine novels and fresh insight into Woolf’s letters, diaries and essays. The progress of Woolf’s thinking is revealed from Bloomsbury aestheticism through her hatred of censorship, corruption and hierarchy to her concern with all aspects of modernism. This book explores the immense range of social and political issues behind her search for new forms of narrative. ![]() Buy the book here

Buy the book here

Jane Marcus, New Feminist Essays on Virginia Woolf, Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1981.

Herbert Marder, Feminism and Art: A Study of Virginia Woolf, New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1968.

Allen McLaurin, Virginia Woolf: The Echoes Enslaved, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

Makiko Minow Pinkney, Virginia Woolf and the Problem of the Subject, Brighton: Harvester, 1987.

A.D. Moody, Virginia Woolf, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1963.

Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautman (eds), The Letters of Virginia Woolf, 6 Vols, London: Hogarth Press, 1975-84.

Roger Poole, The Unknown Virginia Woolf, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

Sue Roe and Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Phyllis Rose, Woman of Letters: A Life of Virginia Woolf, New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

N.C. Thakur, The Symbolism of Virginia Woolf, London: Oxford University Press, 1965.

Eric Warner (ed), Virginia Woolf: A Centenary Perspective, London: Macmillan, 1984.

Jane Wheare, Virginia Woolf, Methuen, 1989.

Leonard Woolf, An Autobiography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World, Berkley: University of California Press, 1986.

© Roy Johnson 2005

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

Virginia Woolf – life and works

Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens

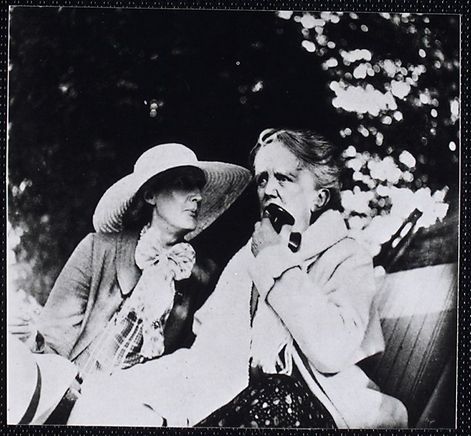

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with

Vita (Victoria Mary) Sackville-West (1892-1962) was a prolific poet and novelist – though she is probably best known for her writing on gardens and her affair with