a chronicle of events, literature, and politics

1866. George Eliot, Felix Holt the Radical; Elizabeth Gaskell, Wives and Daughters; Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; Fyodor Dostoyeski, Crime and Punishment; A.C. Swinburne, Poems and Ballads

1867. Russia sells Alaska to America for $7 million. The Second Reform Bill – votes extended to most middle-class men. Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach.

1868. Benjamin Disraeli becomes Prime Minister. Trades Union Congress formed. Robert Browning, The Ring and the Book. Wilkie Collins The Moonstone.

1869. Suez canal opened. J.S. Mill, The Subjection of Women (written in 1860). Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy. Margarine is developed. Hungarian Emanuel Herman invents the picture postcard. Anthony Trollope, Phineas Finn. Girton College (for women) opened in Cambridge

1870. Papal infallibility announced. French declare war against Prussia – and are heavily defeated. Paris occupied. Married Women’s Property Act. Forster’s Education Act (compulsory full-time schooling for under tens).

1871. Paris commune declared – then crushed (by the French). Limited voting introduced in Britain. Emile Zola begins Le Rougon Maquart cycle of novels. George Eliot Middlemarch. Religious entry tests abolished at Oxford and Cambridge.

1872. Thomas Hardy, Under the Greenwood Tree. Christina Rossetti, Goblin Market.

1873. Walter Pater, The Renaissance, John Stuart Mill, Autobiography (posthumous)

1874. Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd ; Parliament reduces the working week to 56.5 hours. Tolstoy, Anna Karenina. First Impressionist exhibition in Paris.

1875. Disraeli buys Suez Canal shares, gaining a controlling interest for Britain. Anthony Trollope, The Way We Live Now

1876. Queen Victoria declared Empress of India. Bell invents the telephone. George Eliot, Daniel Deronda ; Thomas Hardy, The Hand of Ethelberta; Henry James, Roderick Hudson.

1877. Henry James, The American; Zola, L’Assommoir. Phonograph invented by Edison.

1878. Thomas Hardy, The Return of the Native, Henry James, The Europeans. University of London admits women to degrees. Electric street lighting in London.

1879. Henrik Ibsen, A Doll’s House, George Meredith, The Egoist; Henry James, Daisy Miller.

1880. First Anglo-Boer war in South Africa. Education Act makes schooling compulsory up to the age of ten.

1881. The Natural History Museum is opened. President Garfield of the USA and Tsar Alexander II of Russia are assassinated. Henry James, Washington Square, The Portrait of a Lady. D.G. Rossetti, Ballads and Sonnets; Henrik Ibsen, Ghosts. Gilbert and Sullivan write Patience, a comic opera that pokes fun at the aesthetic movement.

1883. Robert Louis Stephenson, Treasure Island. Olive Schreiner The Story of an African Farm

1884. The franchise is extended by the Third Reform Bill. Mark Twain, Huckleberry Finn; F. Engels, The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State; Walter Besant gives a lecture entitled ‘The Art of Fiction’ and Henry James responds with an essay of the same title. First Oxford English Dictionary

1885. Radio waves discovered. Internal combustion engine invented. Death of General Gordon at Khartoum. Zola, Germinal. Rider Haggard King Solomon’s Mines

1886. Daimler produces first motor car. Thomas Hardy, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Henry James, The Bostonians.

1887. Thomas Hardy, The Woodlanders. Conan Doyle A Study in Scarlet (first Sherlock Holmes story)

1888. English Football League founded. George Eastman develops the Kodak camera. English vet John Dunlop patents the pneumatic tyre. Rudyard Kipling, Plain Tales from the Hills; Henry James, The Aspern Papers. Jack the Ripper murders in Whitechapel, London

1889. Eiffel Tower built for the Paris Centennial Exposition. Coca-Cola developed in Atlanta. 10,000 dockers strike in London. Rudyard Kipling, Barrack-Room Ballads; Henrik Ibsen, Hedda Gabler

1891. Work starts on the Trans-Siberian railway. The Prince of Wales appears in a libel case about cheating at cards. Anglo-American copyright agreement. Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Gissing, New Grub Street, Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray ; Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

1892. James Dewar invents the vacuum flask. First edition of Vogue appears in New York. Tchaikovsky, The Nutcracker. Thomas Hardy, The Well Beloved. Keir Hardy first Labour MP.

1893. First motor cars built by Karl Benz in Germany and Henry Ford in the USA. Alexander Graham Bell makes the first long-distance telephone call. Whitcome Judson patents the zip fastener. Independent Labour Party founded.

1894. Manchester ship canal opens. Dreyfus affair fanned by anti-Semitism in France. Rudyard Kipling, Jungle Books.

1895. X-rays discovered. Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest. First radio broadcast by Marconi. First moving images displayed by French cinematographer.

1896. Wireless telegraphy invented. Abyssinians defeat occupying Italian forces – first defeat of colonising power by natives. Thomas Hardy, Jude the Obscure; Anton Chekhov, The Seagull. Daily Mail founded.

1897. Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Henry James, The Spoils of Poynton, What Masie Knew; Bram Stoker, Dracula.

1898. Second Anglo-Boer War begins. Henry James, The Turn of the Screw ; Thomas Hardy, Wessex Poems; George Bernard Shaw, Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant

1899. British military disasters in South-Africa. Henry James, The Awkward Age; Kate Chopin, The Awakening; Anton Chekhov, Uncle Vanya

1900. Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim

1901. Queen Victoria dies — Edwardian period begins. Rudyard Kipling, Kim

1902. Henry James, The Wings of the Dove; Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

1903. First flight in heavier-than-air machine by Wright brothers in USA. James, The Ambassadors

1904. Henry James, The Golden Bowl; Anton Chekhov, The Cherry Orchard

© Roy Johnson 2009

More on How-To

More on literary studies

More on writing skills

Eugene Onegin

Eugene Onegin A Hero of Our Time

A Hero of Our Time Dead Souls

Dead Souls Notes from Underground

Notes from Underground

From the House of the Dead

From the House of the Dead Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment The Brothers Karamazov

The Brothers Karamazov  Anna Karennina

Anna Karennina War and Peace

War and Peace Fathers and Sons

Fathers and Sons

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

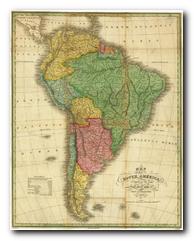

The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco. Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo.

The location of the novel is Costaguana, a fictional country on the western seaboard of South America, and the focus of events is in its capital Sulaco, where a silver mine has been inherited by English-born Charles Gould but is controlled by American capitalists in San Francisco. Competing military factions plunge the country in a state of civil war, and Gould tries desperately to keep the mine working. Amidst political chaos, he dispatches a huge consignment of silver, putting it into the hands of the eponymous hero, the incorruptible Capataz de Cargadores, Nostromo. A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-semitism.

A great deal of the narrative tension in this long novel turns on who knows what about whom, and many of the key scenes are drenched in dramatic irony built on coincidences which have all the improbability of the nineteenth century novel hanging about them. At one point a completely new character suddenly appears as a stowaway on a boat, and then improbably survives a collision with another ship in the dark by hanging onto the other boat’s anchor. And this is merely a plot device allowing him to transmit misleading information to his captors – and incidentally allows Conrad to indulge in a rather unpleasant bout of anti-semitism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended.

The Complete Critical Guide to Joseph Conrad is a good introduction to Conrad criticism. It includes a potted biography, an outline of the stories and novels, and pointers towards the main critical writings – from the early comments by his contemporaries to critics of the present day. Also includes a thorough bibliography which covers biography, criticism in books and articles, plus pointers towards specialist Conrad journals. These guides are very popular. Recommended. The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes