tutorial, commentary, study resources, plot, and web links

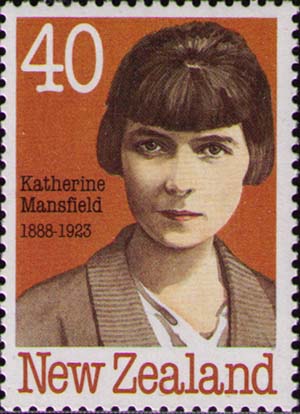

A Cup of Tea was written on 11 January 1922 in the space of just ‘4-5 hours’ and was published in a popular magazine the Story-teller in May of the same year. It then appeared in the collection The Dove’s Nest and Other Stories compiled by Katherine Mansfield’s husband John Middleton Murry and published in 1923.

A Cup of Tea – critical commentary

The ostensible point of the story is that a rich and self-regarding woman has her complacency disturbed. On a whim, she makes what she thinks of as a charitable gesture to a destitute lower-class girl, only to discover (via her husband) that the girl has qualities that she herself does not possess.

However, there is another reading of the story buried subtly in the narrative and its dialogue. Rosemary is a rich and spoiled woman with a self-indulgent lifestyle who feels that her sudden encounter with a girl off the streets could be ‘an adventure … like something out of a novel by Dostoevsky’ – which in a sense that Rosemary would not understand, it does turn out to be.

She takes the girl back home, ushers her into her private bedroom, and undresses her (in the sense of taking off her hat and coat). She has the intention of leading her into another room for tea but does not do so. When the girl begins to cry, she puts her arm around the girl’s ‘thin, bird-like shoulders’ and promises to look after her.

When Rosemary’s husband Philip interrupts, the young girl gives what is clearly a false name (‘Smith’) and is strangely unfazed by the situation in which she finds herself: she is ‘strangely still and unafraid’. Rosemary describes their encounter in terms of procurement: ‘I picked her up in Curzon Street. She’s a real pick-up’.

Philip, the husband, is shocked by two things – first, by how attractive the girl is, and second by the inappropriate relationship that exists between the two women. He asks satirically if ‘Miss Smith’ will be dining with them, in which case he might be forced to look up The Milliner’s Gazette.

The surface implication of this remark is that the girl might be an unemployed shop girl who is sponging off his wealthy wife, but at a deeper level there is a suggestion that she might be a prostitute of some kind. At that time in the early twentieth century, the employment of single females in occupations such as milliner (hat maker) shop assistant, and other forms of casual jobs was regarded as loosely equivalent to prostitution. This suggestion in the story is reinforced by what happens next. Rosemary pays off the girl with three pound notes and sends her on her way.

The sting in the tale for Rosemary is that she wonders if she, for all the wealth and luxury in her life, lacks the animal magnetism possessed by the lower-class young girl which has left her husband Philip ‘bowled over’ after a single glance.

Narrative voice

The literary quality in the story comes largely from the skillful manner in which Mansfield creates a fluid narrative voice which combines an engagement with her subject, her readers, and even (to some extent) with herself as an identifiable narrator.

Technically, the story starts in third person narrative mode: ‘Rosemary Fell was not exactly beautiful’ – but that ‘not exactly’ establishes a conversational style and an attitude to the character. She raises questions, cancels thoughts (‘No, not Peter—Michael’) employs slang (‘a duck of a boy’) and speaks to an imaginary interlocutor (‘she would go to Paris as you and I would go to Bond Street’).

It is also interesting to note that her use of fashionable exaggeration is remarkably similar to that being used today – almost a hundred years later: (‘her husband absolutely adored her … the man who kept it was ridiculously fond of serving her’). This captures perfectly the speech mannerisms and the attitudes of the nouveau riche milieu in which the story is set.

A Cup of Tea – study resources

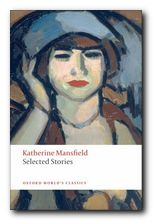

Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Three published collections of stories – Kindle edition – Amazon UK

The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Wordsworth Classics paperback edition – Amazon UK

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Penguin Classics paperback edition – Amazon UK

Katherine Mansfield Megapack

The complete stories and poems in Kindle edition – Amazon UK

Katherine Mansfield’s Collected Works

Three published collections of stories – Kindle edition – Amazon US

The Collected Short Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Wordsworth Classics paperback edition – Amazon US

The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield

Penguin Classics paperback edition – Amazon US

Katherine Mansfield Megapack

The complete stories and poems in Kindle edition – Amazon US

A Cup of Tea – plot summary

Rosemary Fell is a socially poised young woman who has been married for two years to a rich and devoted husband. She shops in the fashionable and expensive part of the West-End in London. An ingratiating antiques dealer shows her a small enamelled box which she covets but asks to be put by for her.

Coming out of the shop into the rain, she is accosted by a poor young woman who asks for the price of a cup of tea. Rosemary sees the incident as a potential adventure and invites the girl back home.

When they reach the house Rosemary takes the girl into her bedroom and relieves her of her hat and coat. The girl breaks down in tears and says she cannot go on any longer.

Rosemary gives the girl tea and sandwiches, whilst she herself smokes cigarettes. This relieves the girl, and they are about to start a conversation when they are interrupted by the arrival of Rosemary’s husband Philip.

Philip takes Rosemary into an adjoining room and asks her what is going on. She explains that she is merely trying to be kind to a poor girl. But Philip points out that the girl is remarkably pretty, but the relationship not desirable.

Rosemary gives the girl some money, and she leaves, after which Rosemary asks her husband if she can have the enamel box she has seen – but what she really wants to know from him is if she is pretty or not.

Katherine Mansfield – web links

Katherine Mansfield at Mantex

Life and works, biography, a close reading, and critical essays

Katherine Mansfield at Wikipedia

Biography, legacy, works, biographies, films and adaptations

Katherine Mansfield at Online Books

Collections of her short stories available at a variety of online sources

Not Under Forty

A charming collection of literary essays by Willa Cather, which includes a discussion of Katherine Mansfield.

Katherine Mansfield at Gutenberg

Free downloadable versions of her stories in a variety of digital formats

Hogarth Press first editions

Annotated gallery of original first edition book jacket covers from the Hogarth Press, including Mansfield’s ‘Prelude’

Katherine Mansfield’s Modernist Aesthetic

An academic essay by Annie Pfeifer at Yale University’s Modernism Lab

The Katherine Mansfield Society

Newsletter, events, essay prize, resources, yearbook

Katherine Mansfield Birthplace

Biography, birthplace, links to essays, exhibitions

Katherine Mansfield Website

New biography, relationships, photographs, uncollected stories

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Katherine Mansfield

Twentieth century literature

More on the Bloomsbury Group

More on short stories

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. Best-selling title, written by the author of these web pages.

Studying Fiction is an introduction to the basic concepts and technical terms you need when making a study of stories and novels. It shows you how to understand literary analysis by explaining its elements one at a time, then showing them at work in short stories which are reproduced as part of the book. Topics covered include – setting, characters, story, point of view, symbolism, narrators, theme, construction, metaphors, irony, prose style, tone, and interpretation. The book also contains self-assessment exercises, so you can check your understanding of each topic. Best-selling title, written by the author of these web pages.

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention.

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention. This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose.

This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose. This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone.

This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone. Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts.

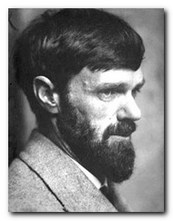

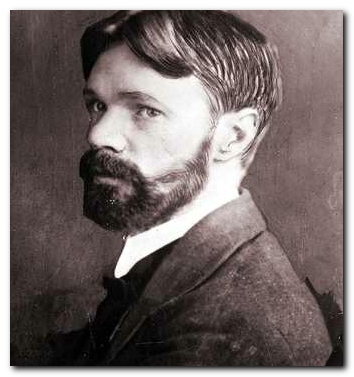

Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts. D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.

D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

Studying Fiction

Studying Fiction Sons and Lovers

Sons and Lovers The Rainbow

The Rainbow