Hogarth Press first edition book jacket designs

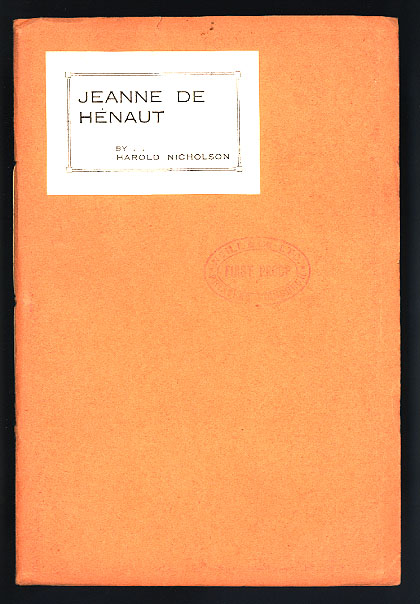

Harold Nicolson, Jeanne de Hénaut (1924)

Only 55 copies were printed. This copy has the printer’s “First Proof” stamp and the date “8 Nov. 1924” on the front cover. The author’s name is spelled “Nicholson” on the proof, but this was corrected before publication. This is the only known copy of the First Proof.

Hogarth Press studies

Woolf’s-head Publishing is a wonderful collection of cover designs, book jackets, and illustrations – but also a beautiful example of book production in its own right. It was produced as an exhibition catalogue and has quite rightly gone on to enjoy an independent life of its own. This book is a genuine collector’s item, and only months after its first publication it started to win awards for its design and production values. Anyone with the slightest interest in book production, graphic design, typography, or Bloomsbury will want to own a copy the minute they clap eyes on it.

Woolf’s-head Publishing is a wonderful collection of cover designs, book jackets, and illustrations – but also a beautiful example of book production in its own right. It was produced as an exhibition catalogue and has quite rightly gone on to enjoy an independent life of its own. This book is a genuine collector’s item, and only months after its first publication it started to win awards for its design and production values. Anyone with the slightest interest in book production, graphic design, typography, or Bloomsbury will want to own a copy the minute they clap eyes on it.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: Hogarth Press, 1917-41 John Willis brings the remarkable story of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s success as publishers to life. He generates interesting thumbnail sketches of all the Hogarth Press authors, which brings both them and the books they wrote into sharp focus. He also follows the development of many of its best-selling titles, and there’s a full account of the social and cultural development of the press. This is a scholarly work with extensive footnotes, bibliographies, and suggestions for further reading – but most of all it is a very readable study in cultural history.

Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers: Hogarth Press, 1917-41 John Willis brings the remarkable story of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s success as publishers to life. He generates interesting thumbnail sketches of all the Hogarth Press authors, which brings both them and the books they wrote into sharp focus. He also follows the development of many of its best-selling titles, and there’s a full account of the social and cultural development of the press. This is a scholarly work with extensive footnotes, bibliographies, and suggestions for further reading – but most of all it is a very readable study in cultural history.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2005

Good page layout

Good page layout