preparing for literary studies at undergraduate level

This book is designed to make students of literature think more deeply about the subject. It explains the development of English Literature as an academic discipline and poses fundamental questions about the activity – such as ‘What is English [Literature] and what is studying it supposed to mean?’ Robert Eaglestone’s book aims to help students prepare for studying literature at undergraduate level. He offers a gentle introduction to literary theory – but without lots of jargon.

If students read what he has to say, they will certainly be more confident in confronting some of the challenges and contradictions which exist in literary studies in universities. For instance, tutors commonly deduct marks from students for poor written expression – and quite right too. Yet why do so many literary critics get published when their work is almost unintelligible? These are questions worth asking. He explains the rise in ‘Eng Lit’ and uncovers some of the hidden assumptions which lie beneath the surface of traditional attitudes to it. This is in fact an explanation of the ideology of ‘Eng. Lit.’ – but he cleverly avoids even using the term.

If students read what he has to say, they will certainly be more confident in confronting some of the challenges and contradictions which exist in literary studies in universities. For instance, tutors commonly deduct marks from students for poor written expression – and quite right too. Yet why do so many literary critics get published when their work is almost unintelligible? These are questions worth asking. He explains the rise in ‘Eng Lit’ and uncovers some of the hidden assumptions which lie beneath the surface of traditional attitudes to it. This is in fact an explanation of the ideology of ‘Eng. Lit.’ – but he cleverly avoids even using the term.

He unpacks the concept of the literary canon and looks in detail at Shakespeare studies as a prime example. This is followed by issues of interpretation which are summed up in the expressions ‘the intentional fallacy’ and ‘the death of the author’.

The latter parts of the book are devoted to considering the relationships between English Literature and cultural identity, politics, and educational policy. His consideration of these larger strategic issues make me think that this book will be as valuable to teachers as to students. It will help them clarify their ideas about their objectives and teaching strategies in the classroom.

There is an excellent and deeply annotated bibliography. Any student [or teacher] reading even a few of the titles he recommends will be well prepared to put their own approach to literary studies into a well-informed ideological context. [But they don’t have to mention the term.]

© Roy Johnson 2009

Robert Eaglestone, Doing English: A guide for literature students, London: Routledge, 3rd edition 2009, pp.192, ISBN: 0415284236

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

Yet when his wife bears him a male child (Paul junior) the son is immediately removed from his primary sources of emotional comfort – first of all from his mother because she dies, then from his beloved nurse, Polly Toodles, because Dombey fires her. Dombey then submits his son to the dubious care of his stupid sister Mrs Chick and her friend Miss Tox. Even worse, he subsequently sends Paul to the appalling establishment run by the fraudulent Mrs Pipchin in Brighton. She neglects the children placed in her care to an almost criminal extent.

Yet when his wife bears him a male child (Paul junior) the son is immediately removed from his primary sources of emotional comfort – first of all from his mother because she dies, then from his beloved nurse, Polly Toodles, because Dombey fires her. Dombey then submits his son to the dubious care of his stupid sister Mrs Chick and her friend Miss Tox. Even worse, he subsequently sends Paul to the appalling establishment run by the fraudulent Mrs Pipchin in Brighton. She neglects the children placed in her care to an almost criminal extent.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters.

Pickwick Papers (1836-37) was Dickens’ first big success. It was issued in twenty monthly parts and is not so much a novel as a series of loosely linked sketches and changing characters featured in reports to the Pickwick Club. These recount comic excursions to Rochester, Dingley Dell, and Bath; duels and elopements; Christmas festivities; Mr Pickwick inadvertently entering the bedroom of a middle-aged lady at night; and in the end a happy marriage. Much light-hearted fun, and a host of memorable characters. Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

Oliver Twist (1837-38) expresses Dickens’ sense of the vulnerability of children. Oliver is a foundling, raised in a workhouse, who escapes suffering by running off to London. There he falls into the hands of a gang of thieves controlled by the infamous Fagin. He is pursued by the sinister figure of Monks who has secret information about him. The plot centres on the twin issues of personal identity and a secret inheritance (which surface again in Great Expectations). Emigration, prison, and violent death punctuate a cascade of dramatic events. This is the early Victorian novel in fine melodramatic form. Recommended for beginners to Dickens.

English solicitor Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to visit Count Dracula, who has bought properties in London. He is hospitably received, but then is held prisoner in the castle, where he encounters three female vampires. Harker writes letters to his fiancée and employer asking for help, but Dracula intercepts them. Dracula then takes a boat journey to England. On the journey the entire crew disappear one by one. The ship is driven ashore at Whitby, Yorkshire during a violent storm.

English solicitor Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to visit Count Dracula, who has bought properties in London. He is hospitably received, but then is held prisoner in the castle, where he encounters three female vampires. Harker writes letters to his fiancée and employer asking for help, but Dracula intercepts them. Dracula then takes a boat journey to England. On the journey the entire crew disappear one by one. The ship is driven ashore at Whitby, Yorkshire during a violent storm. Van Helsing reads Lucy’s diaries and letters, then visits Mina and Jonathan in Exeter and reads the typed copies of their journals, which Mina has made. He then recruits John Seward to visit Lucy’s tomb, which turns out to be empty when they visit it at night. On returning in the daylight however, they find her there. He then recruits Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris, and the four men confront Lucy in her vampire mode outside the tomb. Next day they return in the daylight and Arthur drives a stake through her heart, following which Van Helsing cuts off her head.

Van Helsing reads Lucy’s diaries and letters, then visits Mina and Jonathan in Exeter and reads the typed copies of their journals, which Mina has made. He then recruits John Seward to visit Lucy’s tomb, which turns out to be empty when they visit it at night. On returning in the daylight however, they find her there. He then recruits Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris, and the four men confront Lucy in her vampire mode outside the tomb. Next day they return in the daylight and Arthur drives a stake through her heart, following which Van Helsing cuts off her head.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

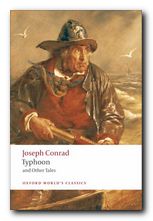

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent