tutorials, synopses, commentaries, and study resources

This is an ongoing collection of tutorials and study guides featuring the short stories of Virginia Woolf. The earliest story dates from 1906 and the latest from 1940, written for American Vogue magazine shortly before her death. They are presented here in alphabetical order of title. The list will be updated as new titles are added.

![]() A Haunted House

A Haunted House

![]() A Simple Melody

A Simple Melody

![]() A Summing Up

A Summing Up

![]() An Unwritten Novel

An Unwritten Novel

![]() Ancestors

Ancestors

![]() Happiness

Happiness

![]() In the Orchard

In the Orchard

![]() Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens

![]() Moments of Being

Moments of Being

![]() Monday or Tuesday

Monday or Tuesday

![]() Phyllis and Rosamond

Phyllis and Rosamond

![]() Solid Objects

Solid Objects

![]() Sympathy

Sympathy

![]() The Evening Party

The Evening Party

![]() The Introduction

The Introduction

![]() The Lady in the Looking-Glass

The Lady in the Looking-Glass

![]() The Legacy

The Legacy

![]() The Man who Loved his Kind

The Man who Loved his Kind

![]() The Mark on the Wall

The Mark on the Wall

![]() The Mysterious Case of Miss V

The Mysterious Case of Miss V

![]() The New Dress

The New Dress

![]() The Shooting Party

The Shooting Party

![]() The String Quartet

The String Quartet

![]() The Symbol

The Symbol

![]() The Watering Place

The Watering Place

![]() Together and Apart

Together and Apart

Virginia Woolf podcast

A eulogy to words

Study resources

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Vintage Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon UK

![]() The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

The Complete Shorter Fiction – Harcourt edition – Amazon US

![]() Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

Monday or Tuesday and Other Stories – Gutenberg.org

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon UK

![]() Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

Kew Gardens and Other Stories – Hogarth reprint – Amazon US

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics – Amazon UK

![]() The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

The Mark on the Wall – Oxford World Classics – Amazon US

![]() The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle

The Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle

![]() Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf’s works

Hyper-Concordance to Virginia Woolf’s works

![]() Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

Virginia Woolf at Wikipedia – biographical notes, links

![]() Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Virginia Woolf at Mantex – tutorials, web links, study resources

Writing app

Mont Blanc pen – the Virginia Woolf special edition

Further reading

![]() Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Quentin Bell. Virginia Woolf: A Biography. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

![]() Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hermione Lee. Virginia Woolf. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

![]() Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Nicholas Marsh. Virginia Woolf, the Novels. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

![]() John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

John Mepham, Virginia Woolf. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

![]() Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

Natalya Reinhold, ed. Woolf Across Cultures. New York: Pace University Press, 2004.

![]() Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Michael Rosenthal, Virginia Woolf: A Critical Study. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

![]() Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

![]() Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. New York: Harvest Books, 2002.

![]() Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Alex Zwerdling, Virginia Woolf and the Real World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Other works by Virginia Woolf

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

Kew Gardens is a collection of experimental short stories in which Woolf tested out ideas and techniques which she then later incorporated into her novels. After Chekhov, they represent the most important development in the modern short story as a literary form. Incident and narrative are replaced by evocations of mood, poetic imagery, philosophic reflection, and subtleties of composition and structure. The shortest piece, ‘Monday or Tuesday’, is a one-page wonder of compression. This collection is a cornerstone of literary modernism. No other writer – with the possible exception of Nadine Gordimer, has taken the short story as a literary genre as far as this.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

Virginia Woolf is a readable and well illustrated biography by John Lehmann, who at one point worked as her assistant and business partner at the Hogarth Press. It is described by the blurb as ‘A critical biography of Virginia Woolf containing illustrations that are a record of the Bloomsbury Group and the literary and artistic world that surrounded a writer who is immensely popular today’. This is an attractive and very accessible introduction to the subject which has been very popular with readers ever since it was first published..

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

© Roy Johnson 2014

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Lolita

Lolita Pale Fire

Pale Fire Pnin

Pnin Speak Memory

Speak Memory Despair

Despair Mary

Mary Laughter in the Dark

Laughter in the Dark The Gift

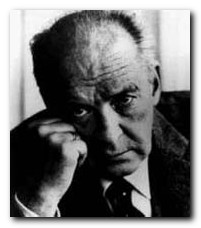

The Gift 1899. Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg on April 23 [the same birthday as Shakespeare]. His father was a prominent jurist, liberal politician, and a member of the Duma (Russia’s first parliament). His mother was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic family.

1899. Vladimir Nabokov was born in St Petersburg on April 23 [the same birthday as Shakespeare]. His father was a prominent jurist, liberal politician, and a member of the Duma (Russia’s first parliament). His mother was the daughter of a wealthy aristocratic family.