the life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s pet Spaniel

Flush a biography (1933) is a work that combines fictional biography with Virginia Woolf’s love of ‘letters’ and her interst in writers’ lives. And of course it also encompasses the fanciful side of her imagination, being the life story of a dog. But it’s a famous dog – the pet spaniel of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. It’s a short piece of work — a jeux d’esprit — and it’s written with a witty lightness of style which nevertheless touches on important themes.

Virginia Woolf was interested in writing life histories throughout the whole of her career. She was the daughter of a professional biographer (Leslie Stephen) and some of her earliest work featured sketches of famous cultural figures, some of whom were visitors to her home. In her middle period she produced the magnificent fantasy biography Orlando, and one of her last full length non-fictional works was Roger Fry, a portrait study of her friend and fellow Bloomsbury artist.

Virginia Woolf was interested in writing life histories throughout the whole of her career. She was the daughter of a professional biographer (Leslie Stephen) and some of her earliest work featured sketches of famous cultural figures, some of whom were visitors to her home. In her middle period she produced the magnificent fantasy biography Orlando, and one of her last full length non-fictional works was Roger Fry, a portrait study of her friend and fellow Bloomsbury artist.

Woolf pokes fun at ancestral snobbery in this fantasy by describing Flush’s family history as if it were recorded in the same way as yhat of nobles and aristocracy – to the detriment of humans. In fact the dog’s biography is used as an excuse for conjouring up a picture of upper class London in the early nineteenth century – the solidity of Wimpole Street, and the interior of the famous Barratt house at number fifty. The description is from a dog’s point of view – smells first and foremost, furniture no more than blurred shapes, and rooms over-decorated to the point where nothing is quite what it seems.

In a sense, Woolf is using the story to describe her own Victorian childhood home at Hyde Park Gate which she found so atmospherically oppressive. Of course the story of Elizabeth Barrett’s constricted life as a semi-invalid is well known, and the central conceit of the tale is that since Flush has to endure imprisonment in the claustrophobic bedroom, he learns to suppress his instincts for movement and freedom in the outside world in the same way his mistress has done herself.

The very eventlessness of this existence is grist to Woolf’s creative mill. She is not at all fazed by the lack of plot or dramatic events. Her interest is in the way consciousness deals with the passage of time. The texture of a day is relayed through its sounds and smells, and the manner in which events outside the “cushioned and firelit cave” are suggested by subtle shifts in household routines. This is an account written, after all, by someone who produced the long essay on life in stasis, On Being Ill

But then the monotony is broken by the arrival of “the hooded man” – Robert Browning, who comes to pay court to the invalid. Flush takes a couple of bites at the great man’s trousers, but then rather whimsically decides to love him after all. However, the mood of the story takes a sombre then quite sinister shift when Flush is kidnapped by dog thieves. Woolf conjures up a Dickensian vision of a Whitechapel populated by vicious criminals, beggars, and prostitutes – “a world that Miss Barratt had never seen, had never guessed at”.

These scenes make a profound impression on Elizabeth Barrett, and this edition is packed with evidence that they featured in her later poetry, as well as proof that many of the dramatic incidents of the biography are based on descriptions which occur in her daily letters to Robert Browning.

The two poets eventually marry in secret and then elope to live in Italy, where Flush discovers that a more free and democratic spirit prevails than in gloomy London. Indeed he is happy to grow old there, dozing in the sun of Florence, and reflecting on human foolishness when he becomes surrounded by the mid-Victorian craze for spiritualism. Poets, statesmen, and Lords gather at the Browning’s table in the Casa Guidi to gaze into a glass ball which purports to offer “spirits of the sun”.

It is a light and witty piece of writing which has been an unjustly neglected part of Woolf’s oeuvre. But despite the fanciful subject, it is quite clear that she is offering readers a critique of class snobbery, human foibles, social stratification, and the ‘unexamined’ life of a female poet.

© Roy Johnson 2011

Virginia Woolf, Flush: A Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp.132, ISBN: 0199539294

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis Amerika

Amerika

Although it purports to cover five decades, most of the book is devoted to his bohemian wanderings in the 1920s, which he spent oscillating between Spain and the

Although it purports to cover five decades, most of the book is devoted to his bohemian wanderings in the 1920s, which he spent oscillating between Spain and the

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

Harold Nicolson (1886-1968) was born into an upper middle-class family in Tehran, where his father (Lord Carnock) was the British ambassador to Persia. as it then was. He was educated at Wellington College then Balliol College Oxford, where he graduated with a third-class degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1908 and was posted to Constantinople where he became a specialist in Balkan affairs. In 1910 he met

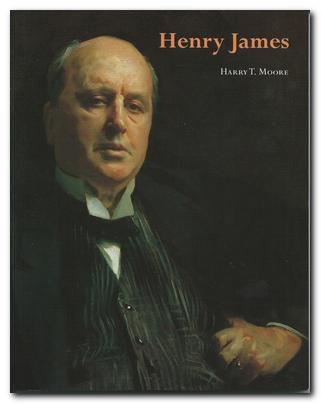

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors