tutorial, summaries, study resources, further reading

Dubliners (1914) is James Joyce’s first major work – a ground-breaking collection of short stories dealing with the moribund lives of a cast of mostly lower-middle-class characters through pointedly undramatic events chosen to illustrate the crippling effects of family, religion, and nationality. He spent seven years working on them, even though he suspected publishing them might be difficult at the time – and he was right. He submitted the stories to seventeen publishers over the space of many years before they were finally accepted.

This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century, ending with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. The book caused controversy when it first appeared, and was banned in Ireland almost immediately upon publication, the first of many of Joyce’s works to be censored or banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories.

This collection of vignettes features both real and imaginary figures in Dublin life around the turn of the century, ending with the most famous of all Joyce’s stories – ‘The Dead’. The book caused controversy when it first appeared, and was banned in Ireland almost immediately upon publication, the first of many of Joyce’s works to be censored or banned in his native country. Dubliners is now widely regarded as a seminal collection of modern short stories.

Contemporary readers may wonder what all the fuss was about; but one hundred years ago at the start of the twentieth century any references to body functions, sexuality, and anti-religious sentiment was more or less unthinkable in Ireland – which is the principal reason why Joyce left his homeland in 1906, never to return.

Dubliners is a carefully arranged set of miniatures in which he strips away all the decorations and flourishes of late Victorian prose. What remains is a sparse yet lyrical exposure of small moments of revelation – which he called ‘epiphanies’. Like other modernists, such as Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf, Joyce minimised the dramatic element of the short story in favour of symbolic meaning and a more static aesthetic. Instead of the surprise endings and dramatic twists of the typical nineteenth-century short story, Joyce offers subtle, understated character studies, revelations of mood and atmosphere, and small moments in life which reveal something about larger issues.

James Joyce – portrait

Dubliners – structure

Joyce gave his publisher Grant Richards the following account of his ideas for the structure of his collection:

“My intention was to write a chapter of the moral history of my country, and I chose Dublin for the scene because that city seemed to me the centre of paralysis. I have tried to present it to the indifferent public under four of its aspects: childhood, adolescence, maturity, and public life. The stories are arranged in this order. I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness and with the conviction that he is a very bold man who dares to alter in the presentment, still more to deform, whatever he has seen and heard.”

Section I, Childhood contains – The Sisters, An Encounter, and Araby (the most anthologised of the stories).

Section II, Adolescence is made up of – Eveline, After the Race, Two Gallants, and The Boarding House.

Section III, Maturity is also made up of four stories – A Little Cloud, Counterparts, Clay, and A Painful Case.

Section IV, Public Life is made up of – Ivy Day in the Committee Room, A Mother, Grace, and the structurally different The Dead.

Study resources

![]() Dubliners – Penguin Modern Classics – Amazon UK

Dubliners – Penguin Modern Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Dubliners – Penguin Modern Classics – Amazon US

Dubliners – Penguin Modern Classics – Amazon US

![]() Dubliners – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon UK

Dubliners – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon UK

![]() Dubliners – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon US

Dubliners – Oxford World’s Classics – Amazon US

![]() Dubliners – Norton Critical Editions – Amazon US

Dubliners – Norton Critical Editions – Amazon US

![]() Dubliners – eBook version at Project Gutenberg

Dubliners – eBook version at Project Gutenberg

![]() The Dead – 1987 film version by John Huston on DVD – Amazon UK

The Dead – 1987 film version by John Huston on DVD – Amazon UK

![]() Dubliners – Naxos audio CD version – Amazon UK

Dubliners – Naxos audio CD version – Amazon UK

![]() Dubliners – audioBook version at LibriVox

Dubliners – audioBook version at LibriVox

![]() Dubliners – York Notes (Advanced) – Amazon UK

Dubliners – York Notes (Advanced) – Amazon UK

![]() Dubliners – Cliffs Notes study guide – Amazon UK

Dubliners – Cliffs Notes study guide – Amazon UK

![]() James Joyce: A Critical Guide – Amazon UK

James Joyce: A Critical Guide – Amazon UK

![]() The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce – Amazon UK

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce – Amazon UK

![]() James Joyce: Texts and Contexts – Amazon UK

James Joyce: Texts and Contexts – Amazon UK

Dubliners – chapter summaries

The Sisters – After the priest Father Flynn dies, a young boy who was close to him and his family deal with it only superficially. The events force him to examine their relationship and cause him to see himself as an individual for the first time.

An Encounter – Two schoolboys playing truant from school encounter an elderly man, who turns out to be a pervert.

Araby – A boy falls in love with the sister of his friend, but fails in his quest to buy her a worthy gift from the Araby bazaar. He becomes aware of the pain and unfulfilled dreams of the adult world.

Eveline – A young woman abandons her plans to leave Ireland with a sailor, and faces instead the prospect of remaining with her abusive father in order to help raise her younger siblings.

After the Race – College student Jimmy Doyle tries to fit in with his wealthy friends, and fails.

Two Gallants – Two con men, Lenehan and Corley, find a maid who is willing to steal from her employer.

The Boarding House – Mrs. Mooney successfully manoeuvres her daughter Polly into an upwardly mobile marriage with her lodger Mr. Doran.

A Little Cloud – Little Chandler’s dinner with his old friend Ignatius Gallaher casts fresh light on his own failed literary dreams. The story reflects also on Chandler’s mood upon realizing his baby son has replaced him as the centre of his wife’s affections.

Counterparts – Farrington, a lumbering alcoholic Irish scrivener, takes out his frustration in pubs and on his son Tom.

Clay – The old maid Maria, a laundress, celebrates Halloween with her former foster child Joe Donnelly and his family.

A Painful Case – Mr. Duffy rebuffs Mrs. Sinico, then four years later realizes he has condemned her to loneliness and death.

Ivy Day in the Committee Room – Minor Irish politicians fail to live up to the memory of Charles Stewart Parnell.

A Mother – Mrs. Kearney tries to win a place of pride for her daughter, Kathleen, in the Irish cultural movement, by starring her in a series of concerts, but ultimately fails.

Grace – After Mr. Kernan injures himself falling down the stairs in a bar, his friends try to reform him through Catholicism.

The Dead – Gabriel Conroy attends a party his wife, has an epiphany about the nature of life and death.

Dubliners – video short

Epiphanies

When Joyce wrote Dubliners it was at a time when he was seeking to strip bare what he saw as the smugness and hypocrisy which Britain had inherited from its Victorian epoch. To do this he felt that a new sense of realism and honesty was necessary, and in literary terms this meant dealing with subjects which were not always particularly pleasant or uplifting, but might on the contrary be concerned with the sadder and negative aspects of life. Even these, he felt, should be depicted with scrupulous honesty and objectivity.

He postulated the notion (as did Virginia Woolf only a few years later) that revelations about the truths of life are available to us in special moments – fleeting episodes, snatches of conversation, or a sudden dawning of awareness which as he said, was like ‘the revelation of the whatness of a thing’. To describe these experiences he borrowed the term ‘epiphanies’ from his religious background. It means ‘a manifestation’ or ‘showing forth’ – but he gave it a secular meaning. The sometimes negative and transient nature of these moments are underscored by Richard Ellman, Joyce’s biographer:

The unpalatable epiphanies often include things to be got rid of, examples of fatuity or imperceptiveness, caught deftly in a conversational exchange of two or three sentences.

But Joyce also believed that the author of a work should not be present in his story – nudging the reader’s elbow, telling him what to think and feel – but should scrupulously remove himself from the work and let it speak for itself. [This was a notion he had inherited from Flaubert.] Consequently these epiphanies when they occur are often understated: Joyce does not specially draw our attention to what is going on but leaves us to work out or sense the implications for ourselves.

To make matters even more subtle, the revelations, when they occur, are not always fully evident to the fictional character undergoing the experience – but they are nonetheless available to the attentive reader.

Howth, Dublin

The short story

Joyce was well aware of developments in the modern short story. He was an admirer of Flaubert, whose precision of style was influential in the late nineteenth century. He also knew the work of Maupassant and Checkhov, who had done a great deal to bring realistic, everyday subjects to prose fiction – often featuring raw, painful, and frank exposures of negative aspects of daily life. Joyce followed these tendencies by removing suspense or any overt drama from his stories. Instead, he focused his attention on what he called ‘epiphanies’.

The stories in Dubliners are arranged in rising order of length and complexity, and also in the age of the central character. They are best read in that sequence by first time readers. The early stories are brief character sketches, studies in mood, and revelations of desperation and failure. The sequence ends with the longest and very celebrated story, The Dead, which combines Irish culture and politics with a poignant study in personal weakness and disappointment.

Joyce writes in a spare, undecorated, almost Spartan style. As he said of this approach himself: ‘I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness.’ There are very few figures of speech, no exaggeration, and no rhetorical flourishes – until the very last story in the collection. Most of the time Joyce shows events from the point of view of the principal character in each story – and in fact his style and choice of vocabulary closely reflects their consciousness.

![]() more on the short story

more on the short story

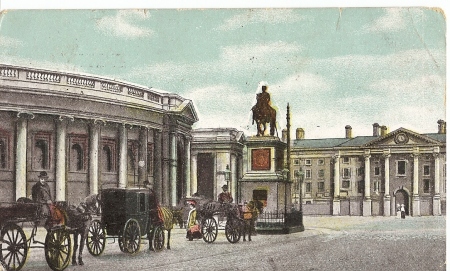

Trinity College Dublin (TCD)

Further reading

![]() Anthony Burgess, Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce, Andre Deutsch, 1973.

Anthony Burgess, Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce, Andre Deutsch, 1973.

![]() Robert H. Deming (ed), James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, 2 Vols, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

Robert H. Deming (ed), James Joyce: The Critical Heritage, 2 Vols, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1970.

![]() Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, Oxford University Press, 1959.

Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, Oxford University Press, 1959.

![]() Richard Ellmann and Stuart Gilbert (eds), The Letters of James Joyce, 3 Vols, Faber, 1957-66.

Richard Ellmann and Stuart Gilbert (eds), The Letters of James Joyce, 3 Vols, Faber, 1957-66.

![]() Seon Givens, James Joyce: Two Decades of Criticism, New York: Vanguard Press, 1963.

Seon Givens, James Joyce: Two Decades of Criticism, New York: Vanguard Press, 1963.

![]() Suzette A. Henke, James Joyce and the Politics of Desire, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1990.

Suzette A. Henke, James Joyce and the Politics of Desire, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1990.

![]() Harry Levin, James Joyce: a Critical Introduction, New York: New Directions, 1960.

Harry Levin, James Joyce: a Critical Introduction, New York: New Directions, 1960.

![]() Colin MacCabe (ed), James Joyce: New Perspectives, Harvester, 1982.

Colin MacCabe (ed), James Joyce: New Perspectives, Harvester, 1982.

![]() W.J. McCormack and Alistair Stead (eds), James Joyce and Modern Literature, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1982.

W.J. McCormack and Alistair Stead (eds), James Joyce and Modern Literature, Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1982.

![]() Dominic Maganiello, Joyce’s Politics. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

Dominic Maganiello, Joyce’s Politics. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

![]() Patrick Parrinder, James Joyce, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Patrick Parrinder, James Joyce, Cambridge University Press, 1984.

![]() C.H. Peake, James Joyce: The Citizen and the Artist, Arnold, 1977.

C.H. Peake, James Joyce: The Citizen and the Artist, Arnold, 1977.

![]() Jean-Michel Rabaté, Joyce Upon the Void, Macmillan, 1991.

Jean-Michel Rabaté, Joyce Upon the Void, Macmillan, 1991.

![]() Lee Spinks, James Joyce: A Critical Guide, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009

Lee Spinks, James Joyce: A Critical Guide, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009

![]() W.Y. Tindall, A Reader’s Guide to James Joyce, Thames and Hudson, 1959.

W.Y. Tindall, A Reader’s Guide to James Joyce, Thames and Hudson, 1959.

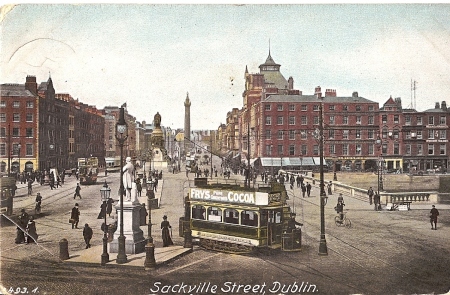

Dublin 1915

Major works by James Joyce

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is Joyce’s first complete novel – a largely autobiographical account of a young man’s struggle with Catholicism and his desire to forge himself as an artist. It features a prose style whose complexity develops in parallel with the growth of the hero, Stephen Dedalus. The early pages are written from a child’s point of view, but then they quickly become more sophisticated. As Stephen struggles with religious belief and the growth of his sexual feelings as a young adult, the prose become more complex and philosophical. In addition to the account of his personal life and a critique of Irish society at the beginning of the last century, it also incorporates the creation of an aesthetic philosophy which was unmistakably that of Joyce himself. The novel ends with Stephen quitting Ireland for good, just as Joyce himself was to do – never to return.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

Ulysses (1922) is one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, and it is certainly Joyce’s most celebrated work. He takes Homer’s Odyssey as a structural framework and uses it as the base to create a complex story of characters moving around Dublin on a single day in June 1904. Each separate chapter is written in a different prose style to reflect its theme or subject. The novel also includes two forms of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique. This was Joyce’s attempt to reproduce the apparently random way in which our perceptions of the world are mixed with our conscious ideas and memories in an unstoppable flow of thought. There is a famous last chapter which is an eighty page unpunctuated soliloquy of a woman as she lies in bed at night, mulling over the events of her life and episodes from the previous day.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce contains eleven essays by an international team of leading Joyce scholars. The topics covered include his debt to Irish and European writers and traditions, his life in Paris, and the relation of his work to the ‘modern’ spirit of sceptical relativism. One essay describes Joyce’s developing achievement in his earlier works (Stephen Hero, Dubliners, and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Another tackles his best-known text, asking the basic question ‘What is Ulysses about, and how can it be read?’ The issue of ‘difficulty’ raised by Finnegans Wake is directly addressed, and the reader is taken through questions of theme, language, structure and meaning, as well as the book’s composition and the history of Wake criticism.

![]() Buy the book at Amazon UK

Buy the book at Amazon UK

![]() Buy the book at Amazon US

Buy the book at Amazon US

James Joyce – web links

![]() James Joyce at Mantex

James Joyce at Mantex

Biographical notes, study guides to the major works, book reviews, studies of the short stories, bibliographies, web links, study resources.

![]() James Joyce at Project Gutenberg

James Joyce at Project Gutenberg

A limited collection of free eTexts in a variety of digital formats.

![]() James Joyce at Wikipedia

James Joyce at Wikipedia

Full biography, social background, interpretation of the major works, religion, music, list of biographies, and external web links.

![]() James Joyce at the Internet Movie Database

James Joyce at the Internet Movie Database

Adaptations for the cinema and television – in various languages. Full details of directors and actors, plus box office, technical credits, and quizzes.

![]() James Joyce Centre in Dublin

James Joyce Centre in Dublin

Exhibition centre, walking tours, lectures, and newsletter. The latest addition is a graphic novel version of ‘Ulysses’.

![]() The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

University of Wisconsin – digitised scans of Finnegans Wake and out-of-print studies on Joyce’s language, plus rare critical studies.

![]() An Annotated Ulysses

An Annotated Ulysses

An online version of Ulysses with hyperlinks giving explanations of obscure and classical references in the text.

![]() Cornell’s James Joyce Collection

Cornell’s James Joyce Collection

Cornell University – a collection of letters, manuscripts, and books documenting the life and work of James Joyce on exhibition in 2005. Particularly strong on Joyce’s early life.

![]() A Bibliography of Scholarship and Criticism

A Bibliography of Scholarship and Criticism

Slightly dated but still useful web-based compilation of criticism and commentary – covers Joyce himself, plus the stories and novels.

© Roy Johnson 2010

More on James Joyce

Twentieth century literature

More on study skills

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

The Bostonians

The Bostonians What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Tess of the d’Urbervilles The Woodlanders

The Woodlanders Wessex Tales

Wessex Tales

Part II. Three years later he meets her again by chance in Le Havre, where she has just arrived from America for her much-anticipated visit. However, she has given all her travellers cheques to her cousin (who she has never met before) to exchange for Francs before they go on to Paris, where he is studying art. The narrator fears that she will never see the cousin again, but he does turn up and reveals himself as an unappetizing bohemian.

Part II. Three years later he meets her again by chance in Le Havre, where she has just arrived from America for her much-anticipated visit. However, she has given all her travellers cheques to her cousin (who she has never met before) to exchange for Francs before they go on to Paris, where he is studying art. The narrator fears that she will never see the cousin again, but he does turn up and reveals himself as an unappetizing bohemian.