19th century master of the short story form

Guy de Maupassant was a prolific and very famous writer in his own lifetime. Between 1880 and 1891 for instance he wrote about 300 short stories, 200 articles, six novels, two plays, and three travel books. He wrote in the heyday of the short story, and it is this literary form for which he is now best remembered. Maupassant was one of the late nineteenth-century writers shaping what was to become the modern short story. His contribution to the genre was to pare down the means of expression and to focus on the effect of the tale.

His stories are not abbreviated novels or rambling prose poems. They tell a story – and often it has a sting in the tail. Like other French writers of the late nineteenth century he was keen to explore ordinary everyday life – often exposing its less appetising and even grim features. I bought this particular collection after watching Jean Renoir’s beautiful film Partie de campagne which is a completely faithful account of the title story. But I was amazed to discover that the full length feature film and masterpiece of the cinema was based on a tale no more than a few pages long.

His stories are not abbreviated novels or rambling prose poems. They tell a story – and often it has a sting in the tail. Like other French writers of the late nineteenth century he was keen to explore ordinary everyday life – often exposing its less appetising and even grim features. I bought this particular collection after watching Jean Renoir’s beautiful film Partie de campagne which is a completely faithful account of the title story. But I was amazed to discover that the full length feature film and masterpiece of the cinema was based on a tale no more than a few pages long.

His style, much influenced by his friend Flaubert, is one of scrupulous clarity. Everything is pared to a minimum, and the material world is rendered in well-chosen detail. His attitude is that of a sceptical realist, with an eye for the tragic and sad elements of life which lead many critics to brand him a pessimist. They may have a point, because it’s remarkable just how many of his stories end with someone’s abrupt death.

He was shortening and concentrating the narrative, stripping it of excrescence. Yet he still drags along some of its traditional features – the whiplash ending for instance. Some of them are not much more than well-articulated anecdotes, but they are usually resolved with an ironic or dramatic twist.

Despite these weaknesses, it’s his contribution to the development of the short story for which he is still respected. It is his stories which are still widely read, not his full-length novels.

[Maupassant] fixes a hard eye on some spot of human life, usually some dreary, ugly, shabby, sordid one, takes up the particle, and squeezes it either till it grimaces or till it bleeds. Sometimes the grimace is very droll, sometimes the wound is very horrible … Monsieur de Maupassant sees human life as a terribly ugly business relieved by the comical.

It’s amazing to think that Henry James, a friend and admirer who wrote those words was writing at the same time – though when considering the compositional crudities in some of these stories, their origin in newspapers and popular magazines should be taken into account.

But this famous terseness of style is not quite so ubiquitous as is often claimed. He is quite prepared to indulge in rhetorical flourishes to make his point – as in this account of a Parisian visiting the provinces:

I wondered: ‘What on earth can I do after dinner?’ I thought how long an evening could be here in this town in the provinces: the slow, grim stroll through unfamiliar streets, the depressing gloom which the solitary traveller feels oozing out of passers by who are complete strangers in every respect, from the provincial cut of their jackets, hats, and trousers to their ways and the local accent, an all-pervading misery which drips from the houses, the shops, the outlandish shapes of the vehicles in the streets, and the generally unaccustomed hubbub, an uneasy sinking of the spirits which prompts you to walk a little quicker as though you were lost in a dangerous, cheerless country and makes you want to go back to your hotel, that loathsome hotel, where your room has been pickled in innumerable dubious smells, where you are not entirely sure about the bed, and where there’s a hair stuck fast in the dried dust at the bottom of the washbasin.

In one of the finest tales in this collection he tackles a subject which has a long and honourable history amongst writers – the story of a man who, as a result of some trivial argument or misplaced notion of pride, suddenly finds that he is about to fight a duel. It also includes his best known – ‘The Necklace’ – another tale which has spawned many variations, as well as ‘Le Horla’, a story which strangely parallels Maupassant’s own descent into premature madness and death, brought on by syphilis.

Later writers such as James Joyce, Katherine Mansfield, and especially Virginia Woolf were to take his stylistic developments further – and bring the short story into closer contact with the prose poem and the philosophic meditation. But connoisseurs of this literary form will always be well rewarded by re-visiting one of the earlier masters of the genre.

© Roy Johnson 2000

Guy de Maupassant, A Day in the Country and Other Stories, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, pp.312, ISBN 0192838636

More on literature

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention.

This tutorial looks at the famous opening passage of Bleak House and examines Dickens’s use of language, simile, and metaphor. It argues that whilst Dickens is often celebrated for the vividness of his descriptions, the true genius of his literary power is in imaginative invention. This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose.

This is the first of two close reading tutorials on Conrad’s early tale An Outpost of Progress. This one looks at the opening of the story and examines the semantic values transmitted in Conrad’s presentation of the narrative. That is, how the meaning(s) of the story are embedded in even the smallest details of of the prose. This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone.

This tutorial looks at one of the opening paragraphs of Katherine Mansfield’s short story The Voyage. It covers the standard features of a writer’s prose style – in the use of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, tone, narrative mode, and figures of speech; but then it singles out the crucial issue of point of view for special attention. Mansfield was one of the only writers to establish a first-rate world literary reputation on the production of short stories alone. Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts.

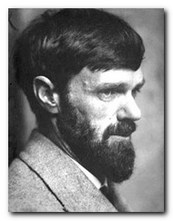

Virginia Woolf used the short story as an experimental platform on which to test out her innovations in language and fictional narrative. This tutorial offers a detailed reading of the whole of the experimental story Monday or Tuesday. It shows how its mixture of lyrical images, speculative thoughts, and fragments of story-line add up to more than the sum of its parts. D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.

D.H.Lawrence was the first world-class writer to have emerged from the working class. His work was passionate, sensual, and controversial. This tutorial looks at the opening paragraphs of his short story Fanny and Annie published in 1922. It considers in particular his use of the rhetorical devices of repetition and alliteration to impart a poetic impressionism to his writing.

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth