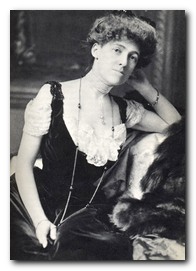

writer, traveller, socialite, gardener, interior designer

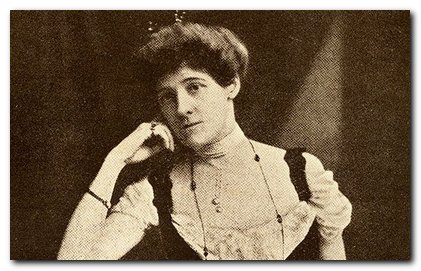

1862. Edith Newbold Jones born into wealthy ‘old money’ family in New York. Her childhood nickname was ‘Pussy Jones’.

1866. Following depreciation on the US Dollar after the Civil war, family move to tour and live in Europe for economic reasons. They live in Paris, Rome, Germany, and Spain. Edith learns French, Italian and German. She inherits a strong sense of place and visual memory from her father.

1872. Family returns to live in New York city, spending the summers in Newport. Edith has a difficult, estranged, and rivalrous relationship with her mother, who has no sympathy with Edith’s artistic and imaginative interests. Edith relieves her solitude by reading in her father’s library, where she becomes acquainted with classics of modern French, Italian, English literature.

1877. First poems published in Atlantic Monthly.

1879. Successful debut into New York society at 17 years old.

1880. The family returns to live in Europe – London, Paris, and Venice. Edith strongly influenced by Ruskin and his concepts of art and architecture.

1882. Death of her father in Cannes. Edith and her mother return to New York.

1885. Edith marries Edward (Teddy) Wharton who does not share her intellectual tastes. It is a marriage for which she is singularly unprepared. They set up home at ‘Penridge Cottage’ (a lavish house) in Newport, and socialize amongst rich New Yorkers (Van Allens, Astors, Vanderbildts) giving parties, boating, and engaging in fashionable archery contests.

1888. Whartons go on lavish Mediterranean cruise paid for with a legacy.

1889. Edith’s stories and poems began to appear in Scribner’s Magazine. She begins to suffer from attacks of asthma, nausea, and fatigue

1892. The Whartons acquire their own first home at Land’s End in Newport – another large-scale house with views on the Atlantic.

1893. French poet and writer Paul Bourget arrives in Newport with a letter of introduction and becomes lifelong friend. He introduces her to his intellectual friends in Paris. She makes intellectual friendship with Edgerton Wynthrop, who becomes her mentor. Meets architect Ogden Codman and commissions him to re-furbish her house at Land’s end.

1897. She co-writes and publishes with Ogden Codman The Decoration of Houses, which is immediately successful and establishes her reputation as an interior designer with a taste for modern style, removing the clutter of the Victorian period from homes. She promotes Codman’s reputation and becomes virtually the project manager of his commissions.

1898. Suffers a nervous collapse and is advised to take a rest-cure by the same doctor who treated Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

1899. Publishes The Greater Inclination, a collection of short stories.

1901. Publishes Crucial Instances a second collection of short stories. Death of her mother in Paris. Edith inherits $90,000 and immediately begins building a huge house (forty-two rooms) in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Edith Wharton’s house – The Mount

1902. Scribners publish The Valley of Indecision, her first novel, which re-creates eighteenth century Italy.

1903. Travels in Europe, and writes Italian Villas and their Gardens. Meets Vernon Lee (Violet Paget) and painter John Singer Sargeant.

1904. Begins friendship with Henry James. She earns more from her writing than he does. They travel together in motor cars named after George Sand’s lovers. The Descent of Man and Other Stories.

1905. The House of Mirth her next novel dealing with modern New York, becomes a best-selling success, following serialization in Scribner’s Magazine.

1906. Edith and her husband spend time in England with Henry James.

1907. Whartons travel through France with Henry James, where Edith meets London Times correspondent W. Morton Fullerton. She starts writing her secret ‘love diary’.

Edith Wharton motoring with Henry James

1908. Edith begins an affair with Fullerton and is passionately moved for the first time in her life. She confides in Henry James, who advises her to ‘sit tight’.

1909. Meets art critic Bernard Berenson in Paris, and for first time does not return to spend the summer at her house, The Mount.

1911. The affair with Fullerton comes to an end, but they remain friends. She establishes an American expatriate salon in Paris and mixes with many cosmopolitan artists – Jean Cocteau, Andre Gide, Serge Diaghilev, and Walter Sickert. Close friendships with Comtesse Rosa de Fitz-James and Comtesse Anna de Noailles. Publishes her novella Ethan Frome which she says ends her period of apprenticeship as a writer.

1912. Edith sells her house The Mount and the same year is formally divorced from her husband Teddy. Publishes The Reef.

1913. Publishes The Custom of the Country.

1914. At the outbreak of the first world war, Edith sets up workshops for working-class women whose husbands have been conscripted. Travels around battlefront in her car with Walter Beery, and writes pro-French articles for the American press. Engages in fund-raising efforts amongst her friends

1916. Death of her friend Henry James. She is awarded the Legion of Honour.

1917. Publishes novella Summer.

1918. Purchases eighteenth-century house, Pavilion Colombie, outside Paris. Restores the house and develops its seven acres of formal gardens

1920. Buys and restores Chateau Sainte-Claire and its gardens in Hyeres, southern Provence. Publishes The Age of Innocence. Begins writing ‘Beatrice Palmato’ – a work about incest.

1921. Awarded the Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Innocence. A great deal of her time is spent developing the extensive gardens on her two estates in Paris and Hyeres.

1923. Makes her final visit to the USA where she is awarded honorary doctorate at Yale university – the first woman to be so honoured. Increasingly reliant on servants – at a time when in the post-war era when working ‘in-service’ was less popular.

1925. Publishes The Writing of Fiction.

1926. Charters yacht for Mediterranean cruise. Visits Bernard Berenson at I Tatti.

1929. Publishes Hudson River Bracketed.

1930. Collection of short stories, Certain People appears.

1933. Another collection of short fiction, Human Nature appears.

1934. Publishes her reminiscences, A Backward Glance. Begins work on a final novel, The Buccaneers, which is never published.

1937. Dies of heart failure and is buried at Versailles.

© Roy Johnson 2011

More on Edith Wharton

More on the novella

More on literary studies

More on short stories

The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The House of Mirth

The House of Mirth

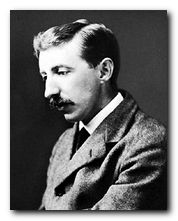

E.M.Forster is often seen as a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of what they called ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also an inner member of

E.M.Forster is often seen as a bridge between the nineteenth and the twentieth century novel. He documents the Edwardian and Georgian periods in a witty and elegant prose, satirising the middle and upper classes he knew so well. He was a friend of Virginia Woolf, with whom he worked out some of the ground rules of literary modernism. These included the concept of what they called ‘tea-tabling’ – making the substance of serious fiction the ordinary events of everyday life. He was also an inner member of  Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Where Angels Fear to Tread – DVD This film version is not a Merchant-Ivory production, although it’s done very much in their style. But it is accurate and entirely sympathetic to the spirit of the novel, possibly even stronger in satirical edge, well acted, and superbly beautiful to watch. Much is made of the visual contrast between the beautiful Italian setting and the straight-laced English capital from which the prudery and imperialist spirit emerges. The lovely Helena Bonham-Carter establishes herself as the perfect English Rose in this her breakthrough production. Helen Mirren is wonderful as the spirited Lilia who defies English prudery and narrow-mindedness and marries for love – with results which manage to upset everyone.

Where Angels Fear to Tread – DVD This film version is not a Merchant-Ivory production, although it’s done very much in their style. But it is accurate and entirely sympathetic to the spirit of the novel, possibly even stronger in satirical edge, well acted, and superbly beautiful to watch. Much is made of the visual contrast between the beautiful Italian setting and the straight-laced English capital from which the prudery and imperialist spirit emerges. The lovely Helena Bonham-Carter establishes herself as the perfect English Rose in this her breakthrough production. Helen Mirren is wonderful as the spirited Lilia who defies English prudery and narrow-mindedness and marries for love – with results which manage to upset everyone. A Room with a View

A Room with a View A Room with a View – DVD This is a Merchant-Ivory production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s still well acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine, Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map.

A Room with a View – DVD This is a Merchant-Ivory production which takes one or two minor liberties with the original novel. But it’s still well acted, with the deliciously pouting Helena Bonham Carter as the heroine, Denholm Eliot as Mr Emerson, Daniel Day-Lewis as a wonderfully pompous Cecil Vyse, and Maggie Smith as the poisonous hanger-on Charlotte. The settings are delightfully poised between Florentine Italy and the home counties stockbroker belt. I’ve watched it several times, and it never ceases to be visually elegant and emotionally well observed. This film was nominated for eight Academy awards when it appeared, and put the Merchant-Ivory team on the cultural map. The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey Howards End

Howards End Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed.

Howards End – DVD This is arguably Forster’s greatest work, and the film lives up to it. It is well acted, with very good performances from Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as the Schlegel sisters, and Anthony Hopkins as the bully Willcox. The locations and details are accurate, and it lives up to the critical, poignant scenes of the original – particularly the conflict between the upper middle-class Wilcoxes and the working-class aspirant Leonard Baskt. This is another adaptation which I have watched several times over, and always been impressed. A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece.

A Passage to India, (1923) was started in 1913 then finished partly in response to the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Snobbish and racist colonial administrators and their wives are contrasted with sympathetically drawn Indian characters. Dr Aziz is groundlessly accused of assaulting a naive English girl on a visit to the mystic Marabar Caves. There is a set piece trial scene, where she dramatically withdraws any charges. The results strengthen the forces of Indian nationalism, which are accurately predicted to be successful ‘after the next European war’ at the end of the novel. Issues of politics, race, and gender, set against vivid descriptions of Chandrapore and memorable evocations of the surrounding landscape. This is generally regarded as Forster’s masterpiece. A Passage to India – DVD This adaptation by David Lean is something of a mixed bag. It’s well organised, reasonably true to the original, and has some visually spectacular scenes. James Fox is convincing as the central character Fielding. But it has tonal inconsistencies, and to cast Alec Guinness as the Indian mystic Godbole is verging on the ridiculous. Nevertheless there is some good cameo acting, particularly Edith Evans as Mrs Moore. Watch out for the Indian signpost half way through that looks as if it’s made out of cardboard.

A Passage to India – DVD This adaptation by David Lean is something of a mixed bag. It’s well organised, reasonably true to the original, and has some visually spectacular scenes. James Fox is convincing as the central character Fielding. But it has tonal inconsistencies, and to cast Alec Guinness as the Indian mystic Godbole is verging on the ridiculous. Nevertheless there is some good cameo acting, particularly Edith Evans as Mrs Moore. Watch out for the Indian signpost half way through that looks as if it’s made out of cardboard. Maurice, (1967) is something from Forster’s bottom drawer. It was written in 1913-14, but not published until after his death. It’s an autobiographical novel of his gay university days which is explicit enough that couldn’t be published in his own lifetime. It’s light, amusing, and fairly inconsequential compared to the novels he wrote whilst pretending to be straight. This poses an interesting critical problem, when you would imagine he could have been more honest and therefore more successful.

Maurice, (1967) is something from Forster’s bottom drawer. It was written in 1913-14, but not published until after his death. It’s an autobiographical novel of his gay university days which is explicit enough that couldn’t be published in his own lifetime. It’s light, amusing, and fairly inconsequential compared to the novels he wrote whilst pretending to be straight. This poses an interesting critical problem, when you would imagine he could have been more honest and therefore more successful. Aspects of the Novel (1927) was originally a series of lectures on the nature of fiction. Forster discusses all the common elements of novels such as story, plot, and character. He shows how they are created, with all the insight of a skilled practitioner. Drawing on examples from classic European literature, he writes in a way which makes it all seem very straightforward and easily comprehensible. This book is highly recommended as an introduction to literary studies.

Aspects of the Novel (1927) was originally a series of lectures on the nature of fiction. Forster discusses all the common elements of novels such as story, plot, and character. He shows how they are created, with all the insight of a skilled practitioner. Drawing on examples from classic European literature, he writes in a way which makes it all seem very straightforward and easily comprehensible. This book is highly recommended as an introduction to literary studies. Collected Short Stories is like a glimpse into Forster’s workshop – where he tried out ideas for his longer fictions. This volume contains his best stories – The Story of a Panic, The Celestial Omnibus, The Road from Colonus, The Machine Stops, and The Eternal Moment. Most were written in the early part of Forster’s long career as a writer. Rich in irony and alive with sharp observations on the surprises in life, the tales often feature violent events, discomforting coincidences, and other odd happenings that throw the characters’ perceptions and beliefs off balance.

Collected Short Stories is like a glimpse into Forster’s workshop – where he tried out ideas for his longer fictions. This volume contains his best stories – The Story of a Panic, The Celestial Omnibus, The Road from Colonus, The Machine Stops, and The Eternal Moment. Most were written in the early part of Forster’s long career as a writer. Rich in irony and alive with sharp observations on the surprises in life, the tales often feature violent events, discomforting coincidences, and other odd happenings that throw the characters’ perceptions and beliefs off balance. E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

E.M.Forster: A Life is a readable and well illustrated biography by P.N. Furbank. This book has been much praised for the sympathetic understanding Nick Furbank brings to Forster’s life and work. It is also a very scholarly book, with plenty of fascinating details of the English literary world during Forster’s surprisingly long life. It has become the ‘standard’ biography, and it is very well written too. Highly recommended.

Ethan Frome is a poor working farmer who lives in a small remote town in Massachusetts. He exists in a state of near poverty with his wife Zeena (Zenobia), a grim, prematurely aged woman who makes hypochondria her hobby and his life a misery. Ethan has travelled as far as Florida and has intellectual aspirations, but he has never been able to develop or fulfil them. Living with them as an unpaid household help is Zeena’s cousin, Mattie Silver, a young woman who has lost her parents.

Ethan Frome is a poor working farmer who lives in a small remote town in Massachusetts. He exists in a state of near poverty with his wife Zeena (Zenobia), a grim, prematurely aged woman who makes hypochondria her hobby and his life a misery. Ethan has travelled as far as Florida and has intellectual aspirations, but he has never been able to develop or fulfil them. Living with them as an unpaid household help is Zeena’s cousin, Mattie Silver, a young woman who has lost her parents.

The Age of Innocence

The Age of Innocence

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

The Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad offers a series of essays by leading Conrad scholars aimed at both students and the general reader. There’s a chronology and overview of Conrad’s life, then chapters that explore significant issues in his major writings, and deal in depth with individual works. These are followed by discussions of the special nature of Conrad’s narrative techniques, his complex relationships with late-Victorian imperialism and with literary Modernism, and his influence on other writers and artists. Each essay provides guidance to further reading, and a concluding chapter surveys the body of Conrad criticism.

Nostromo

Nostromo The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent