essays and reviews on literary and cultural history

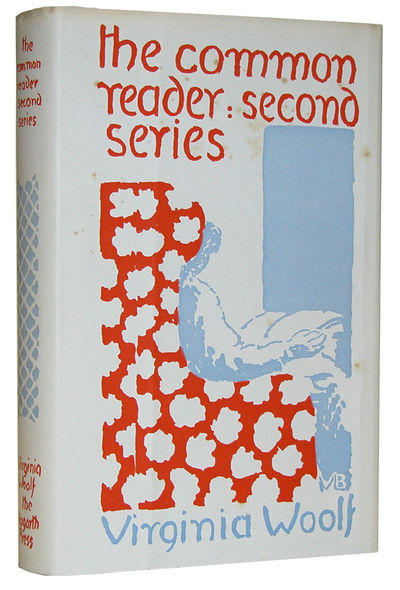

The Common Reader second series (1935) is a collection of essays by Virginia Woolf, the second to be published in her own lifetime. It followed on the success of The Common Reader first series which was published in 1925. Sales of the first volume had surprised both Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard working together at their own enterprise, The Hogarth Press.

The amazing thing is that whilst Woolf was producing all her great novels of the English modernist period, she was also a very productive journalist. This collection includes critical essays, journalism, and book reviews that had previously appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, Life and Letters, The Nation, Vogue, The New York Herald, The Yale Review, and Figaro.

The Common Reader second series – commentary

Following the pattern established in The Common Reader first series the essays are arranged in chronological order by subject. The volume begins with a study of Elizabethan writers and ends with an appreciation of Thomas Hardy – who was a friend of Virginia Woolf’s father, Sir Leslie Stephen. This collection also includes the much-quoted essay “How Should One Read a Book?” in which Woolf offers some profound reflections on the relationship between reader and text. In the first instance her advice appears deceptively simple:

“The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions”.

But it turns out that these instincts and this reason are to be based on a very wide reading experience indeed – of novels, biography, history, and poetry. And the experience itself will be multi-layered, for each book must be compared with others of the same kind, and will finally be judged against the best of its kind. And this is not offered in any spirit of elitism – because she fully realises that much of what we consume as readers will be fairly trivial:

The greater part of any library is nothing but the record of … fleeting moments in the lives of man, women, and donkeys. Every literature, as it grows old, has its rubbish heap, its record of vanished moments and forgotten lives told in faltering and feeble accents that have perished. But if you give yourself up to the delight of rubbish reading, you will be surprised, indeed you will be overcome, by the relics of human life that have been cast out to moulder.

At their best these essays combine a high degree of erudition with the enthusiasm of a writer who is a great lover of literature but who also wants her opinions to be read. Her study of John Donne is part biography, part practical analysis and also an explanation of why he is so ‘modern’ after three hundred years. She explains the relationship between the subjects of his poems and the audience or individual patrons for whom he was writing. She also traces his acceptance of contradictions in himself and life in general which makes him appeal to modern sensibilities.

An essay written on the occasion of the death of Thomas Hardy in 1928 is a survey of his entire work as a novelist. It reveals her deep appreciation of his talent as a creator of powerful human dramas, a countryman and self-taught scholar with poetry at his fingertips, Even though Hardy was a friend of Virginia Woolf’s family she is not at all sycophantic in her judgements. She sees flaws in Jude the Obscure (overly pessimistic) and is even critical of his style.

Her article on Robinson Crusoe is not only an appreciation of the novel in the context of a history of the English novel, but also a meditation on fiction and biography. She takes a topic, brings a great deal of literary erudition to bear upon it, but then relates the topic to a much larger cultural context – as well as generating sparkly digressions that show her to be a passionate reader herself.

The range of her interests is quite breathtaking. There are articles on Swift, on Laurence Sterne, Lord Chesterfield, De Quincey, Hazlitt, Gissing, and on George Meredith, who in her own lifetime had sunk from untouchable fame to a writer who nobody read any more. [Today his critical reputation is more or less extinct.]

It is certainly true that the pace and tone of the literary essay was significantly different one hundred years ago when these examples were composed. Writers even as well informed and technically skilful as Woolf were given license to ramble and generalise in a manner that would not generally be permitted today. But in the essay form she demonstrates a profound cultural intelligence to which the occasional flights of fancy are an acceptable and very stylish bonus extra.

© Roy Johnson 2015

The Common Reader second series – study resources

![]() The Common Reader second series – Amazon UK

The Common Reader second series – Amazon UK

![]() The Common Reader second series – Amazon US

The Common Reader second series – Amazon US

![]() Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon UK

Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon UK

![]() Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon US

Complete Works of Virginia Woolf – Kindle – Amazon US

![]() The Common Reader second series – free eBook formats – Gutenberg

The Common Reader second series – free eBook formats – Gutenberg

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader second series, London: Mariner Books, 2003, pp.336, ISBN: 0156028166

The Common Reader second series – contents

- The Strange Elizabethans

- Donne After Three Centuries

- “The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia”

- “Robinson Crusoe”

- Dorothy Osborne’s “Letters”

- Swift’s “Journal to Stella”

- The “Sentimental Journey”

- Lord Chesterfield’s Letters to His Son

- Two Parsons

- James Woodforde

- The Rev. John Skinner

- Dr. Burney’s Evening Party

- Jack Mytton

- De Quincey’s Autobiography

- Four Figures

- Cowper and Lady Austen

- Beau Brummell

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Dorothy Wordsworth

- William Hazlitt

- Geraldine and Jane

- “Aurora Leigh”

- The Niece of an Earl

- George Gissing

- The Novels of George Meredith

- “I Am Christina Rossetti”

- The Novels of Thomas Hardy

- How Should One Read a Book?

Virginia Woolf – the complete Essays

![]() 1925 — The Common Reader first series

1925 — The Common Reader first series

![]() 1932 — The Common Reader second series

1932 — The Common Reader second series

![]() 1942 — The Death of the Moth

1942 — The Death of the Moth

![]() 1947 — The Moment and Other Essays

1947 — The Moment and Other Essays

![]() 1950 — The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays

1950 — The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays

![]() 1958 — Granite and Rainbow

1958 — Granite and Rainbow

More on Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf – web links

Virginia Woolf – greatest works

Virginia Woolf – criticism

More on the Bloomsbury Group

To the Lighthouse

To the Lighthouse Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’.

Orlando (1928) is one of her lesser-known novels, although it’s critical reputation has risen in recent years. It’s a delightful fantasy which features a character who changes sex part-way through the book – and lives from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. Using this device (which turns out to be strangely credible) Woolf explores issues of gender and identity as her hero-heroine moves through a variety of lives and personal adventures. Orlando starts out as an emissary to the Court of St James, lives through friendships with Swift and Alexander Pope, and ends up motoring through the west end of London on a shopping expedition in the 1920s. The character is loosely based on Vita Sackville-West, who at one time was Woolf’s lover. The novel itself was described by Nigel Nicolson (Sackville-West’s son) as ‘the longest and most charming love-letter in literature’. Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf Washington Square

Washington Square The Aspern Papers

The Aspern Papers The Spoils of Poynton

The Spoils of Poynton

What Masie Knew

What Masie Knew The Ambassadors

The Ambassadors

Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.

The Bostonians (1886) is a novel about the early feminist movement. The heroine Verena Tarrant is an ‘inspirational speaker’ who is taken under the wing of Olive Chancellor, a man-hating suffragette and radical feminist. Trying to pull her in the opposite direction is Basil Ransom, a vigorous young man to whom Verena becomes more and more attracted. The dramatic contest to possess her is played out with some witty and often rather sardonic touches, and as usual James keeps the reader guessing about the outcome until the very last page.